Suu Kyi Concealed the Ground Realities at ICJ

- 22/12/2019

- 0

By Aman Ullah

On 11 December 2019, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, as Agent of the Union of the Republic of Myanmar in the proceedings of ICJ and in her capacity as Union Minister of Foreign Affairs, mentioned that “Mr President, allow me to clarify the use of the term ‘clearance operation’ – ‘nae myay shin lin yeh’ in Myanmar [language]. Its meaning has been distorted. As early as the 1950s, this term has been used during military operations against the Burma Communist Party in Bago Range. Since then, the military has used this expression in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations after attacks by insurgents or terrorists. In the Myanmar language, ‘nae myay shin lin yeh’ – literally ‘clearing of locality’ – simply means to clear an area of insurgents or terrorists.”

Although, Suu Kyi tried to clarify the use of the term ‘clearance operation’ but she did not clarify the legality of that clearance operation that launched in north Arakan since August 2017.

Under the 2008 Constitution, for the President’s designation of ‘military operations areas’ shall be during a state of emergency (Chapter 11) or the President “shall have the right to take appropriate military action, in coordination with the National Defence and Security Council formed in accord with the Constitution, in case of aggression against the Union (213-a).”

Did the President authorize the recent military operations?

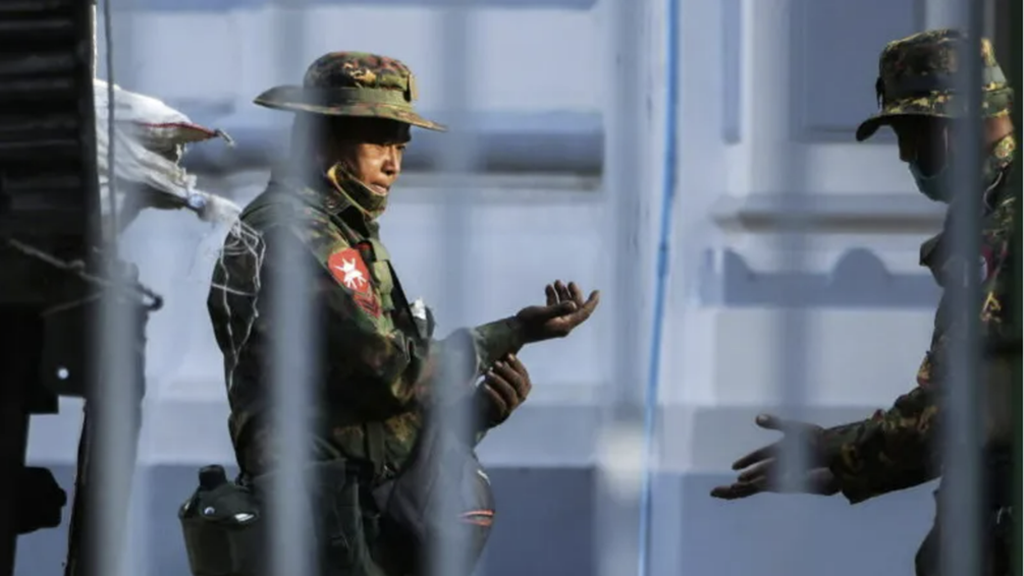

The Office of President Htin Kyaw designated parts of northern Rakhine State as a ‘military operations area’ on 25 August 2017, according to statements by Zaw Htay, Director-General of the Ministry of the Office of the State Counsellor and spokesperson for the State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi. Zaw Htay said that the designation covers the whole of Maungdaw District and was issued as an immediate response to a request from the Office of the Commander-in-Chief of the Tatmadaw. However, there were neither definitive dates to indicate the date of enforcement nor cited clear legal provisions in reference to the President’s designation.

Under the 2008 Constitution, for the President’s designation of ‘military operations areas’ shall be during a state of emergency (Chapter 11) or the President “shall have the right to take appropriate military action, in coordination with the National Defence and Security Council formed in accord with the Constitution, in case of aggression against the Union (213-a).” However, northern Rakhine has neither been declared as a state of emergency nor the National Defence and Security Council has not been formed under the NLD-government. The absence of a declared state of emergency and the absence of a formal National Defence and Security Council meeting calls into question the Constitutional basis for the President’s designation of ‘military operations areas’ in northern Rakhine State.

Article 212 of the Constitution empowers the President to promulgate ordinances for administrative actions requiring immediate actions, with procedural limitations, including the right of parliament to review the ordinance. A review of the weekly Union Government Gazettes published between the 25 August until 31 October 2017 reveals that to date there has been no ordinance or other such promulgation of that the President authorized military operations in northern Rakhine State on 25 August.

Is Rakhine State under a state of emergency?

Myanmar has not declared a constitutional state of emergency over Rakhine State or any part of it, however, a press release from the Ministry of the Office of the State Counsellor was issued on 11 August 2017 stated that parts of northern Rakhine State were subject to a temporary curfew invoked under section 144 of Myanmar’s Criminal Procedure Code. It is unclear whether this curfew remains in force following the attacks on 25 August 2017 and during subsequent security operations.

Section 144 is a key provision under chapter 11 of the Criminal Procedure Code, entitled “Temporary Orders in Urgent Cases of Nuisance or Apprehended Danger.” It provides that a Magistrate may “[d]irect any person to abstain from a certain act or to take certain order with certain property in his possession or under his management, if such Magistrate considers that such direction is likely to prevent, or tends to prevent, obstruction, annoyance or injury, or risk of obstruction, annoyance or injury, to any person lawfully employed, or danger to human life, health or safety, or a disturbance of the public tranquillity, or a riot, or an affray.”

The powers of Judges (Magistrates) under section 144, a carry-over provision from colonial-era criminal law, have in practice been appropriated by the executive and are now exercised by the District Administrator or the Township Administrator of the General Administration Department, part of the Ministry of Home Affairs. The invocation of section 144 orders does in itself not constitute a state of emergency.

What would a state of emergency look like?

Pursuant to article 40 and chapter 11 (comprising articles 410 to 432) of the 2008 Constitution, the President, in coordination and with consent from the National Defence and Security Council, may declare a particular area to be under a temporary state of emergency. The Constitution contemplates three states of emergency:-

1. The Constitution empowers the President to temporarily appropriate executive and legislative powers from lower levels of government, in a particular geographical area (articles 40(a) and 410),

2. The President may request temporary support from the Tatmadaw to perform its functions in a particular geographical area (article 413 a) or may issue an ordinance temporarily transferring executive and judicial powers to the Tatmadaw in a particular geographical area ( article 413 b),

3. The full nationwide transfer of executive, legislative and judicial powers to the Tatmadaw for a period of one year (article 417).

In each instance, a declaration by the President is required to enact a state of emergency.

States of emergency were declared on three occasions under the Union Solidarity and Development Party-led government, led by President Thein Sein from 2011 to 2016. Each of these was a ‘type two’ emergency, under article 40(b) of the Constitution; no ‘type one’ or ‘type three’ emergency under the 2008 Constitution has ever been declared in Myanmar. The most recent state of emergency was declared in February 2015 and covered the conflict-affected Kokang Zone of Shan State.

To date, under the NLD-led government, no constitutional state of emergency has been declared in any part of the country, and the prerequisite formal meeting of the National Defence and Security Council has not been convened under the NLD-led government. The President’s reported designation of parts of northern as a ‘military operations area’ does not constitute a state of emergency declared pursuant to the Constitution.

What rules govern the conduct of security operations?

The State is always required to take all necessary measures intended to prevent deprivations of life, including planning security operations so as to minimize the risk to human life. Where police powers are exercised by military authorities or by other State security forces, such military or other forces are subject to the relevant international standards for law enforcement officials on matters such as use of force and respect for human rights.

The Tatmadaw’s long history of gross and systematic violations of international human rights law and serious humanitarian law violations where there is armed conflict demonstrates that any rules of engagement and codes of conduct for Myanmar’s security forces have in practice failed to curtail, or have even facilitated or effectively authorized, gross human rights violations against people throughout the country. There has been a chronic lack of accountability for security personnel committing or contributing to these crimes.

Unlike in other areas of Myanmar, particularly in Kachin and Shan states, the violence in northern Rakhine State does not fulfill the criteria necessary to classify the situation as an armed conflict according to international law. The fact that military forces were employed to carry out security operations in northern Rakhine State does not of itself mean that those operations are taken pursuant to an armed conflict. In the absence of armed conflict, the State’s security operations must be restricted to law enforcement operations governed by criminal law and human rights law rather than military operations.

Moreover, the security operations are characterized, in northern Rakhine State or anywhere else in Myanmar, the use of force by security forces must comply with protective limitations on the lawful use of force, including principles of necessity and proportionality. Security forces are obliged to abide by constitutional protections and to scrupulously respect international standards governing the use of force.

What are the international standards on the use of force?

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials provide that the use of lethal force by security forces can be made only when it is strictly unavoidable for the purpose of protecting the right to life. Regarding non-lethal force, this also must be employed only as strictly necessary and proportional, and this means it may only be used for limited purposes, such as in self-defence or in the defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent a particular serious act involving a grave threat to life threat or when less extreme means are unavailable.

The 1979 UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials specifies that, where police powers are exercised by military authorities or by State security forces, such military or other forces are subject to the relevant international standards for law enforcement officials on matters such as use of force and respect for human rights.

Can private individuals lawfully participate in security operations?

Credible reports suggest that groups of individuals who are not members of security forces have carried out acts of violence and arson in northern Rakhine State, allegedly with active involvement or acquiescence by security forces. Regardless of the involvement of security forces in the commission of acts by private individuals, such actions constitute crimes that necessitate investigation and prosecution. In instances where security forces enable, facilitate or otherwise contribute to human rights abuses perpetrated by private individuals, or by militias, this will generally also constitute violations of the State’s international human rights law obligations. A failure to intervene to prevent or stop such violence when it happens in the presence of State authorities or when they should be aware of it, or a failure to punish perpetrators in these instances, will also generally constitute a violation of the State’s obligations.

Section 128 of the Criminal Procedure Code authorizes police, as well as magistrates, to acquire “the assistance of any male person, not being an officer, soldier, sailor or airman” to disperse public assemblies and to arrest and confine participants. Under section 127 of the Code, private individuals may be mobilized in this way in instances of unlawful assemblies or assemblies ‘of five or more persons likely to cause a disturbance of the public peace’. There have been no reports of these provisions being invoked recently in northern Rakhine State. Regardless, these provisions in no way permit the crimes of violence and arson.

The use of militias by the Tatmadaw is a long-standing practice in Myanmar. Article 340 of the Constitution states that “With the approval of the National Defence and Security Council, the Defence Services has the authority to administer the participation of the entire people in the Security and Defence of the Union. The strategy of the people’s militia shall be carried out under the leadership of the Defence Services.” As the National Defence and Security Council has not convened under the NLD government, any new militias raised in northern Rakhine State would have no legal basis under Myanmar’s Constitution.

Thus, here, in her statement, Suu Kyi did not mention the legality of the clearance operation that launched in the north Arakan since August 2019. In the name of this clearance operation, the Myanmar security forces purposely destroyed the property of the Rohingyas, targeting their houses, fields, food stocks, crops, livestock and even trees, to render the possibility of the Rohingya returning to normal lives and livelihoods in the future in northern Rakhine almost impossible.

The recent mass exodus of almost 700,000 Rohingya civilians from Rakhine state in Myanmar to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, created a humanitarian crisis that seized the attention of the world. As documented by international medical staff and service providers operating in Bangladesh, many civilians bear the physical and psychological scars of brutal sexual assault. The assaults were allegedly perpetrated by members of the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw), at times acting in concert with members of local militias, in the course of the military “clearance” operations in October 2016 and August 2017 characterized by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights as “ethnic cleansing”. The widespread threat and use of sexual violence were integral to their strategy, humiliating, terrorizing and collectively punishing the Rohingya community and serving as a calculated tool to force them to flee their homelands and prevent their return. Violence was visited upon women, including pregnant women, who are seen as custodians and propagators of ethnic identity, as well as on young children, who represent the future of the group.

Moreover, Suu Kyi also stated the court that, “Mr President, there are those who wish to externalize accountability for alleged war crimes committed in Rakhine, almost automatically, without proper reflection. Some of the United Nations human rights mandates relied upon in the Application presented by The Gambia have even suggested that there cannot be accountability through Myanmar’s military justice system. This not only contradicts Article 20(b) of the Constitution of Myanmar, it undercuts painstaking domestic efforts relevant to the establishment of cooperation between the military and the civilian government in Myanmar, in the context of a Constitution that needs to be amended to complete the process of democratization.”

She further stated that “Please bear in mind this complex situation and the challenge to sovereignty and security in our country when you are assessing the intent of those who attempted to deal with the rebellion. Surely, under the circumstances, genocidal intent cannot be the only hypothesis.”

Here, we want to borrow a few lines from her own writing, she wrote in her book ‘Freedom from Fear’ that, “Where there is no justice there can be no secure peace. The Universal Human Rights recognizes that ‘if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression”. (Freedom from Fear, new addition, 1995, p.177). However, Suu Kyi never ever considered that the Rohingyas are also human being, they also have the right to revolt against the tyranny, against the oppression when they have no recourse. Once she claimed that it was “not ethnic cleansing” and “Muslims have been targeted but also Buddhists have been subject to violence. There’s fear on both sides.”

Hence, Suu Kyi, as Agent of the Union of the Republic of Myanmar in the ICJ’s proceedings and in her capacity as Union Minister of Foreign Affairs, tries to lie, to conceal and to withhold the ground realities in the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Through concealing and withholding realities, she tries to misguide not only the court and the honorable judges but also the whole world with her ill will in order to legalize the unconstitutional clearance operation.