For Rohingya refugees, internet ban severs ties to the outside world

- 11/03/2020

- 0

By Verena Hölzl, The New Humanitarian

‘Provide us half our rations, but give us back the internet.’

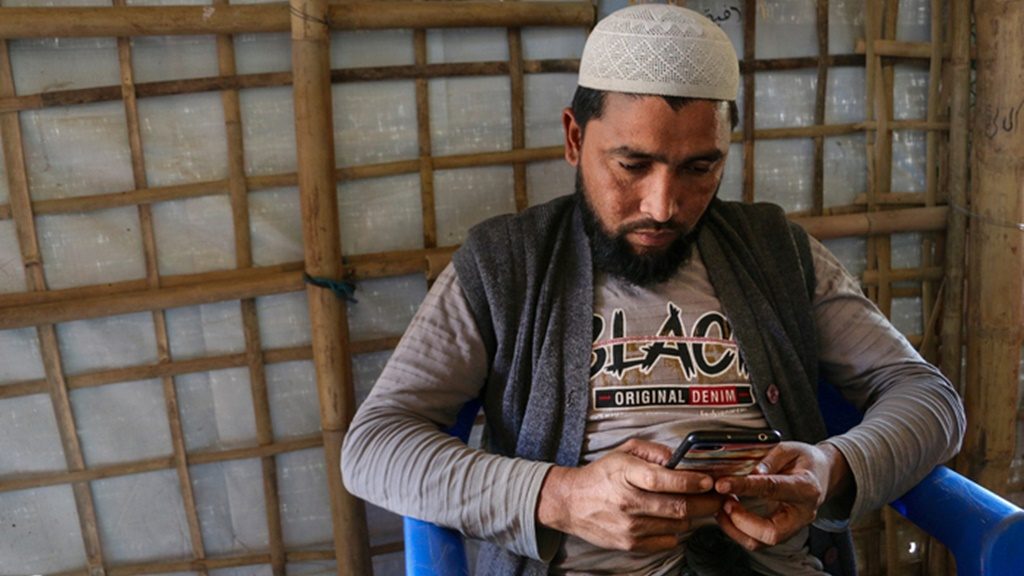

“Sometimes, you can barely say ‘salaam alaikum’ before the call drops again,” he said, a desperate grimace lining his face.

It’s especially hard to reach family still in Rakhine, where Myanmar’s government has also imposed an internet blackout across nearly half the state – including Rafique’s former home in Buthidaung, a northern township.

“I don’t know how my brother is, and he doesn’t know how I am.”

He and his brother haven’t spoken in weeks. He relied on a friend in the nearby town of Cox’s Bazar – officially off-limits to refugees – to relay news of their mother’s death in January.

“I don’t know how my brother is, and he doesn’t know how I am,” he said.

Rights groups say the internet ban is further isolating the Rohingya, making an already marginalised group even more disconnected. Roughly 700,000 Rohingya surged into the camps starting in August 2017, fleeing a military purge from their homes in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. More than two years later, some 900,000 people, including previous generations of refugees, live in ageing bamboo-and-tarpaulin tents with no timeline for a safe return.

Tightening restrictions

Bangladeshi officials have said the mobile phone ban is in place because of security concerns. Many Rohingya believe it’s another punitive measure in a camp crackdown that escalated last year, after a government plan to send thousands of refugees home to Myanmar fizzled, and refugees staged a separate mass demonstration commemorating the two-year anniversary of their flight from Myanmar.

Since then, the government has banned mobile phones for the Rohingya and tightened restrictions on aid groups – at the time, the government accused some NGOs of encouraging refugees to resist repatriation.

Checkpoints have also mushroomed around the camps, and – in some parts – the army has started building fences with watchtowers, which would prevent refugees from leaving the strictly controlled camp areas.

“We are living like in a zoo,” said Mohammed Eleyas, a Rohingya civil society leader. “Everyone can come take information and pictures and do their work. Only we can’t.”

Some Rohingya camp leaders told The New Humanitarian the government had ordered them to confiscate phones.

For Eleyas, the restrictions are a reminder of life in segregated Rakhine State, where owning a phone could get Rohingya arrested. While he was grateful to Bangladesh for providing him with a safe place to live, “this is no life,” he said, adding: “All we do here is survive.”

His WhatsApp is filled with contacts for international groups, who rely on him – as a community leader – to gather and share information. But getting in touch with them has become unpredictable. Recently, he missed an interview with a journalist because the phone connection wasn’t strong enough.

The internet shutdown has also affected the flow of valuable remittances from Rohingya relatives in the diaspora. Eleyas said he had been having trouble getting hold of his family abroad to ask for the money he needed to care for his sick mother.

“Please provide us half our rations,” he said in a plea to the government, “but give us back the internet.”

The phone restrictions have also hurt women. In conservative Rohingya society, women are often expected to stay home. For those with phones, the internet allowed them to bypass these limits and connect with friends across the camps or further afield.

“The internet is everything. I can connect with people and get news and education. Google was my master; my university. Now, I feel blind.”

Omal Khair, a young Rohingya woman, said she can only rarely be reached now. “My friends in Malaysia blame me and ask: ‘Why can’t we call you?’” she said.

Other Rohingya speak of feeling increasingly isolated from the world beyond the camps. The International Court of Justice in The Hague has held hearings in a lawsuit accusing Myanmar’s government of committing genocide against the Rohingya. But dozens of refugees told TNH they’re cut off from information and explanations about the case, since their access to online news is so restricted.

“The internet is everything. I can connect with people and get news and education,” said Sawyeddollah, a member of the Rohingya Students Network, a refugee-run organisation focused on education. “Google was my master; my university. Now, I feel blind.”

Complicating the aid response

The internet restrictions have also disrupted communications with and between aid workers.

It has become more complicated and time-consuming to track down people in the camps, some aid workers told TNH. And sharing information about health or security incidents, including photos and videos from refugees, is more difficult.

“Of course, a humanitarian response of this scale is greatly hampered when the internet and mobile phone network gets squeezed,” said Mahbubur Rahman, who coordinates the Communicating with Communities working group, which includes NGOs concerned about getting clearer information to and from people in crises.

Mizanul Rahman, a team leader at Dushtha Shasthya Kendra, a local NGO, said it can sometimes take half an hour just to get through to his office.

“I called my boss five times, and only the sixth time he received my call,” he said.

That lost time can be crucial. Recently, when he found a woman crying after her husband had beaten her, Rahman said he struggled to call the police for help.

Those safety concerns are mirrored by Rafique, who is a majhi – a Rohingya appointed by the army as quasi-leaders in small sections of the camps. The other night, a boy in his part of the camps was beaten up. When he couldn’t get through to the police, he had to walk to the nearest police post to ask for help in person.

The government counterpart he reports to, as well as other refugees, frequently blame him when he’s unreachable: “They told me: ‘If we don’t get you, what do you even have a phone for?’”

Searching for a signal

The telecom blackout doesn’t only affect the refugees. It has also frustrated Bangladeshis who live in the surrounding communities, straining already frayed relations between locals and the Rohingya.

“The government shut down the internet because of the Rohingya,” said Manik, who runs a snack shop near the refugee camps.

These days, he often can’t reach the salesman who sells him his products: the phone reception is too sporadic. “We want our network back at full speed,” he said.

And even government representatives aren’t spared. Hafiz, a local official, said coordinating the government’s business in the camps had become a pain because the majhis were often unreachable by phone.

“We’ve been struggling ourselves,” he said. “But we can’t help it. It’s a government order.”

Some Rohingya have managed to find their way around the internet ban, at least occasionally.

Rafique said staff at an NGO office once shared their WiFi password with him. And there are parts of the camp where mobile reception is clearer – brief windows of connectivity that are traded carefully among the refugees.

Rafique once paid a rickshaw driver to take him to an area an hour away because he had heard there was an internet signal there – a costly endeavour for most Rohingya, who aren’t allowed to work in Bangladesh.

On a hill overlooking the sprawling camps, Mohammed Alom stood switching his SIM cards, then moved around with his phone thrust to the sky, trying to catch a signal.

“Without communication, how can we share our feelings?” he asked.