FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT IN RAKHINE STATE | Report by Independent Rakhine Initiative

- 13/04/2020

- 0

By Independent Rakhine Initiative

Perhaps more than any other human right, freedom of movement underpins the ability of individuals and communities to live free and dignified lives, and is instrumental for the enjoyment of other rights, including access to healthcare, education and livelihoods. In Rakhine State, restrictions on freedom of movement contribute to the marginalization and exclusion of all communities but are central to the continued persecution of the Rohingya population.

Despite significant international pressure to redress these problematic policies and implement the recommendations of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, in recent years the Government of Myanmar has failed to take the steps necessary to significantly ease movement restrictions.

While conflict between the Arakan Army and the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) creates legitimate grounds for the imposition of new, albeit limited, restrictions, the reality is that individuals and communities across Rakhine State continue to face arbitrary and often discriminatory policies and practices that unduly infringe on their right to freedom of movement.

By sharing the experiences and voices of individuals from five of Rakhine State’s diverse ethnic communities (Hindu, Kaman, Maramagyi, Rakhine and Rohingya), we aim to provide an understanding of current movement dynamics across the state and to provide a platform for the government, as well as its national and international partners, to collaborate on the lifting of all restrictions on movement.

To access IRI’s full findings

To see our recommendations and guide to advocacy on Freedom of Movement

To see the recommendations in matrix form

Preface in Light of the COVID-19 Crisis

March 31, 2020

As the world reels from the spread of COVID-19, it would seem like a strange time for IRI to share a report on Freedom of Movement in Rakhine State. The release of this report, which has been more than one year in the making, has unhappily coincided with a global crisis in which governments around the world are imposing limits on movement for the sake of public welfare. As we note in our analysis, restrictions on freedom of movement can be justified if they are limited and proportionate; the COVID-19 crisis provides a case-in-point for why such restrictions can be considered legitimate. As a Yangon- and Sittwe-based project, we are supportive of the efforts of the Government of Myanmar to limit the spread of the virus and mitigate its impact on its population.

It is precisely for this reason that we have chosen to release this report now. While our data collection and analyis pre-date the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, our findings and recommendations remain more relevant than ever. In combatting the virus, it is necessary to ensure that individuals from all communities – especially those from extremely vulnerable communities, including undocumented individuals, IDPs, and conflict-affected people – have free and equitable access to healthcare. Those seeking care should not be burdened by discriminatory permission requirements or extortion at checkpoints. Curfews should not be used as rationale for denying healthcare access, township hospitals should not bar people from entry because of their religion, and Muslims should not have to pay for security escorts to accompany their ambulances to health care facilities. Humanitarian access should be permitted for non-governmental organizations seeking to provide critical necessities including healthcare, food, water and other life-saving assistance. Blanket bans on internet access that prevent community access to critical information about COVID-19 should be lifted. And the government should clearly communicate the risks of the virus and mitigation measures through public health and awareness-raising campaigns.

These recommendations and others are listed in our Roadmap for Lifting Restrictions on Freedom of Movement. But while the COVID-19 crisis will clearly require a rebalancing of some of the measures we have proposed in the Roadmap with new public health realities, this does not mean the government is justified in keeping in place the existing set of restrictions, particularly those targeted at Rohingya communities and undocumented individuals. Instead, the Government of Myanmar should use the crisis as an opportunity to work more closely with national and international partners to lift unnecessary movement restrictions and ensure the healthcare needs of all communities are met.

See recommendations on access to healthcare relevant to COVID-19

“There are no more checkpoints in the village, but to go to the hospital in Myaung Bway, we have to cross the bridge. At the top of the bridge, we have to pay 1,000 MMK (0.69 USD) per person. If we can’t pay, then they beat us, and we are not allowed to go.” Rohingya, Mrauk U Township

Based on an analysis of its findings, IRI’s Freedom of Movement report finds that:

- Freedom of movement has historically been linked to access to documentation. In Rakhine State, this link has been problematic because it has been built upon the deliberate confiscation of documentation and systemic deprivation of citizenship of the Rohingya community, and further enables discriminatory policies and practices which prevent free movement and constrain access to services for undocumented persons. Ensuring the rights of all communities will require the Government of Myanmar to ensure freedom of movement regardless of ethnicity, religion or citizenship status.

- Possession of citizenship does not guarantee free movement. All communities in Rakhine State experience movement restrictions to some degree regardless of documentation status. The ability of people to move freely is influenced both by identity-related conditions that affect entire communities, as well as circumstantial variables specific to each individual.

- Barriers to movement can be formal and administrative, or informal in nature, resulting from broader socio-political factors. The interplay of formal and informal barriers creates an environment of fear in which some communities have no choice but to limit their own movement, while others are constrained by a lack of access to documentation and the high cost of movement. This environment of fear is enabled by government inaction, including the refusal to hold those who restrict others’ movement to account.

- Movement restrictions against the Rohingya are targeted and discriminatory. The deliberate deprivation of citizenship documentation; long-standing nature of movement restrictions; continued internment of Rohingya in camps; persistent blocks on accessing services; failure to hold violators of human rights abuses accountable; and the targeted nature of movement costs, all understood within the broader context of human rights violations against the community, indicate that restrictions on movement are part of a larger effort to control the Rohingya population. Lifting movement restrictions for the Rohingya must be accompanied by a broader recognition and redressing of the norms and policies that have excluded the Rohingya from Myanmar society, including the laws that govern citizenship itself.

- The conflict between the Arakan Army and Tatmadaw has transformed the landscape in Rakhine State, leading to increased movement restrictions for all communities living in conflict-affected areas. While Rakhine communities have been particularly affected by displacement and arbitrary abuses by security actors, other ethnic groups have also been impacted.

- Ethnic communities including the Kaman, Hindu and Maramagyi also face restrictions on movement, but to differing extents. Kaman and Hindu are less likely to have citizenship documentation (despite Kaman being recognized as a national ethnicity) and thus face more formal barriers to movement. Because of their respective religion, language and/or physical appearance, Kaman and Maramagyi may face discrimination and more informal barriers to movement from government officials and other communities.

“They used to take documents away from people, they took national ID cards. After a few years, people didn’t have documents and they started asking us for Village Departure Certificate. We also needed Form 4 from around this time to cross into other towns. They increased the restrictions one by one. It became worse and worse year by year.” Rohingya, Buthidaung Township

FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT AND CITIZENSHIP

Under international law, all persons have the right to freedom of movement regardless of citizenship status. In Rakhine State, however, freedom of movement has historically been linked to citizenship; holding a citizenship card is the most significant factor in determining whether communities and individuals can move freely. This link is problematic because it is built on a history of identity card confiscation and the ongoing deprivation of citizenship of the Rohingya community. In effect, the government has systematically denied an entire community access to documentation and then barred them from moving freely because they lack documentation.

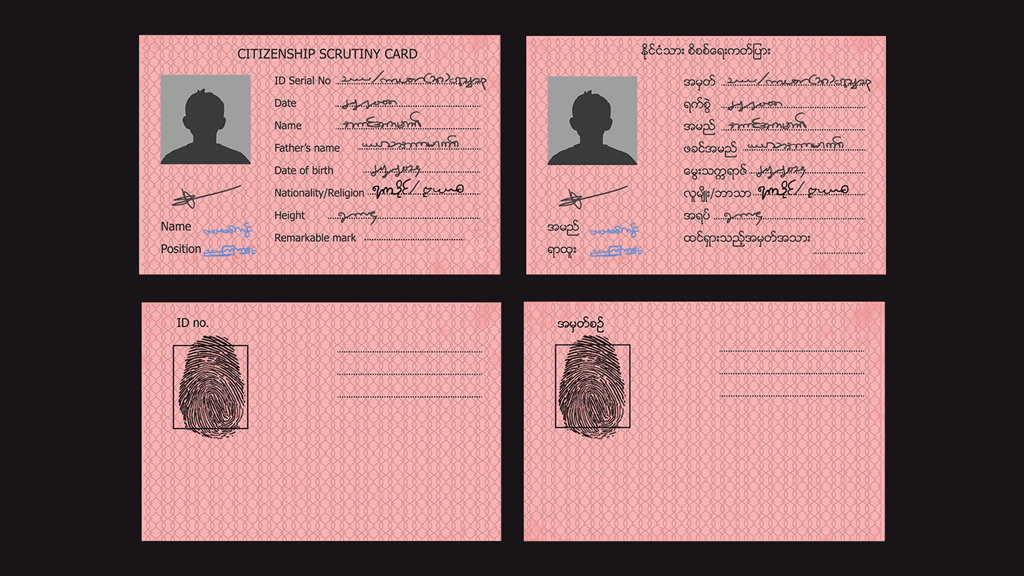

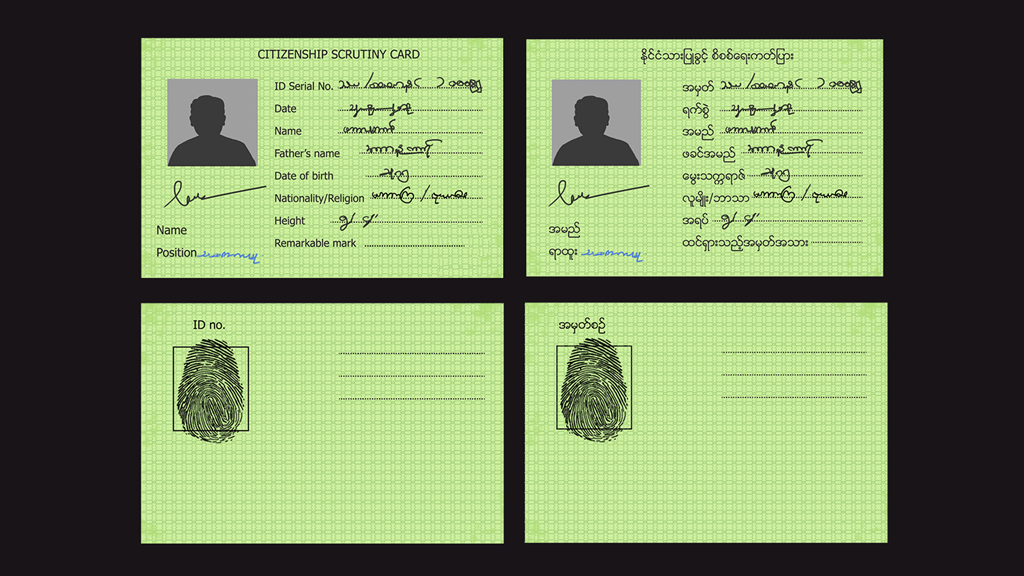

Recent government efforts to increase movement abilities of Rohingya and other undocumented individuals have centred on providing a greater degree of access to documentation. While these efforts should be acknowledged, they remain problematic at best. The National Verification Card (NVC), a card that grants temporary residence while the holder undergoes a citizenship scrutiny process, remains exceedingly unpopular, offering limited benefits to the few who have (willingly or unwillingly) accepted it and increased restrictions for the vast majority who haven’t.

Marginal increases in the number of citizenship decisions granted through the citizenship scrutiny process have provided documentation and eased travel for a small number of individuals, but those who have received new documents continue to be forced to identify as Bengali, and most have received Naturalized Citizenship Scrutiny Cards (NCSC), a sub-tier of citizenship. The government’s limited efforts to improve movement abilities by providing greater access to documentation are further undermined by IRI’s findings in this report, which indicate that possessing citizenship does not guarantee freedom of movement.

Recognizing the problematic nature of the link between free movement and citizenship status and how efforts to provide greater access to documentation have manifested, it is clear that ensuring the right to freedom of movement requires delinking it from citizenship. The Advisory Commission on Rakhine State (RAC) recognizes this need, calling for the government to ensure freedom of movement for all communities regardless of religion, ethnicity and citizenship status (RAC Recommendation 18).

However, while this report calls for delinking freedom of movement from citizenship, it also recognizes the voices of the dozens of Rohingya interviewees who view access to citizenship as the key to moving freely and as a central element critical for their inclusion in Myanmar society. Upholding and protecting the rights of Rohingya communities will require more than just redressing movement restrictions; it will necessitate reforming the policies and norms that have led to their exclusion, including the laws that govern citizenship itself.

‘‘At the checkpoints if the women aren’t ready with their veil removed, they’ll say that you’re disrespecting us, and they will ask us for money or beat us. They will rip off our burkas and slap us in the face, or take any goods that they want…. Less than a month ago, in the Latha village station, I was going into town and there was a new checkpoint that I didn’t know about and so when I got there they said, “Why didn’t you already have your burka off?” And they slapped me in the face. So, they made me pay 1,000 MMK (0.69 USD). I was in the car and the driver wasn’t ready either so they beat him too.’’ Rohingya, Maungdaw Township

FORMAL AND INFORMAL RESTRICTIONS ON MOVEMENT

Restrictions on freedom of movement in Rakhine State are numerous and intersecting, falling broadly under two often mutually reinforcing categories:

Formal restrictions encompass administrative restrictions that are formally imposed by the state. These include:

- Village Departure Certificates or Tauk Kan Sas. Issued by Village Administrators, these forms are needed for Rohingya and those living in conflict-affected areas to travel between village tracts within the same township. They typically cost 1000 MMK.

“I have to get Tauk Kan Sa from the Ogatah, and his house is 30 minutes away from me. Everyone must get the Tauk Kan Sa from the Ogatah, which is difficult if you don’t live near him… If you were to go to a different village, and slept there without the Tauk Kan Sa, they would demand money. If you don’t have any money, they would take you to jail.” Rohingya man from Maungdaw Township

- Form 4s. Issued under a 1997 State Immigration Department Directive that targets ‘Bengali races’ and ‘foreigners’, the Form 4 has been targeted primarily at Rohingya and is needed to travel between townships or outside Rakhine State. Form 4s are obtained from Township and State Immigration Department offices and have a large unofficial cost (between 10,000 and 150,000 MMK for inter-township travel, and between 250,000 to 1,000,000 MMK for interstate travel), making them one of the significant barriers to movement.

“If anyone tries to travel to other townships without [CSC or NCSC] or Form 4, he will be caught when any department’s people (police or military or immigration) meet him and he will be kept in the jail with territorial crime like some people who were caught in Ann and Thandwe while going to Yangon…” Rohingya woman from Aung Mingalara

- Curfews. Curfews are enforced by state security actors and are currently imposed on seven townships in central and northern Rakhine State. Curfews have been specifically targeted at Rohingya communities for years, but more recently they have been extended to cover other communities in areas affected by the increased escalation of conflict between the Arakan Army and Tatmadaw. Curfews extend between 5 or 6 pm and 6 am.

“The Tatmadaw soldiers from station told us that no one can go outside of the village after 6:00 p.m. and before 5:00 a.m. If a person goes out after 6:00 p.m., the Tatmadaw troop said that he or she would be shot by soldiers from the station.” Rakhine woman from Rathedaung Township

- Checkpoints. More than 160 physical checkpoints exist in northern and central Rakhine State, principally along roads, waterways and airports, and at entrances to major settlements and villages. Checkpoints are typically manned by members of security forces including Myanmar Police, Border Guard Police, Myanmar Military (Tatmadaw) and Immigration Department officials.

“We can only go to the hospital during the day, if we need to go to the hospital at night, it’s really difficult. I have two relatives that have died in the night because they were not able to travel to the hospital at night.” Rohingya man in Maungdaw Township

Rohingya woman from Maungdaw

- Restricted Zones. Restricted zones are areas where Muslims are not allowed to travel. These include in township centres in central Rakhine State, including Kyauktaw, Mrauk U, Minbya, Myebon, Pauktaw, Ramree and Rathedaung townships. In addition, most areas of Sittwe Township are inaccessible, as is all of Toungup Township; Muslims are not permitted to stay overnight in Gwa Township.

- Security Escorts, in the form of armed police or other security forces, are required for Muslims traveling between townships, particularly those traveling to Sittwe General Hospital or Sittwe Airport. While these escorts ostensibly exist to protect Muslims from external attack, Muslims are often required to pay unofficial fees to security guards which can severely limit movement and access to services.

“I was threatened by the police that if I did not pay money to them, they would stop the car in the middle of the road and that they would hand us over to the Rakhine. The police threatened that Rakhine will beat us… Everyone is scared for their lives. That was why I said that I would pay money.” Rohingya woman in Sittwe Township

“Our travelling depends on Tatmadaw troops’ movement. If they are deployed near our village, no one can go outside. If we hear the information of military troops movement, all men over 18 and under 50 ages flee the village to safe places due to fear of arbitrary arrests by Tatmadaw.” Rakhine, Buthidaung Township

Informal restrictions are restrictions that stem from a lack of agency that results from broader socio-political factors. These include:

- The intercommunal policing of movement, particularly by Rakhine (and in some cases Hindu) communities who regulate the movement of Rohingya, Kaman and Maramagyi communities through violence and intimidation.

“Local Rakhine people prevent us from travelling to Sittwe. In the past, the police stopped us, but now it is not the police only the Rakhine. They said that, ‘You cannot stay in our Rakhine State, this state is for Rakhine people. You are Muslim. You are from Bangladesh, you cannot go anywhere.’ Sometimes they kill or injure the travelers.” Rohingya man in Pauktaw

- Climate of impunity and abuses by security forces. A lack of accountability for past human rights violations by state security actors, as well as ongoing impunity for security forces and individuals who block others from moving freely, prevents people from moving freely. This includes Rohingya who feel crimes against them will not be prosecuted, and Rakhine who fear arbitrary arrest by security forces.

“Though the government does not prevent us, we can’t go freely because we have fear. And if something happens, we have no justice, and the government also never makes decisions for us equally. Though we need to go outside, to buy or get something, we don’t go because we fear to have problem.” Rohingya woman in Mrauk U

“Our travelling depends on Tatmadaw troops’ movement. If they are deployed near our village, no one can go outside. If we hear the information of military troops movement, all men over 18 and under 50 ages flee the village to safe places due to fear of arbitrary arrests by Tatmadaw.” Rakhine man in Buthidaung

Failure to ensure a secure environment. Instead of prosecuting those who block free movement, the government has failed to create an environment of security, instead using security as a rationale for further restricting the freedom of movement of minorities by requiring security escorts and creating restricted zones. This creates a feeling among communities that the government is purposely imposing restrictions and creating problems for specific communities.

“Yes, we have fear for travelling. When we reach Gwa and Toungup, we fear if someone gives us trouble, who will help us? This kind of fear we have. We have mostly to fear the Rakhine groups. I don’t know exactly if they are told by the government, if they are told to do disturbances like this. What I think is that the government knows everything, but from the backside the government is allowing them to do these troubles.” Kaman woman in Thandwe

In addition, cost serves as a cross-cutting barrier that flows from the application of formal restrictions but is not an official policy. While other communities may also face expensive transport costs and occasional solicitation from officials, the extent to which Rohingya must pay unofficial fees to brokers, government and security officials for legal documentation, movement permissions, security clearances, mandatory police escorts, and checkpoint crossings is unique to that community. Although these costs are most often borne by those without proper documentation, IRI found that even those with permissions, citizenship or NVCs can be asked to pay. Those who can’t may be subject to physical and verbal abuse, as well as arrest and imprisonment.

“Many people died this way. 90% of serious patients die. One woman, about four to five days ago, who is the wife of my father’s friend, died because her husband is poor and could not manage to send her to the hospital. Maybe she could live longer, if she got treatment.” Rohingya, Pauktaw

COMMUNITY EXPERIENCES OF FORMAL (ADMINISTRATIVE) MOVEMENT RESTRICTIONS

Rohingya

Restrictions on movement affect the Rakhine, Kaman, Maramagyi, and Hindu communities the IRI spoke to for this report, and in some cases limit their access to healthcare, education and livelihoods opportunities. The restrictions on the Rohingya community’s freedom of movement are, however, distinguished by their scope, scale, and duration of their imposition.

Discriminatory local orders and policies, requirements for movement permissions and security escorts, and the erection of physical barriers such as checkpoints have served to impede the movement abilities of Rohingya communities and segregate them from broader society in Rakhine State, in many cases severely limiting their access to services as a result. Restrictions on movement can vary geographically and affect those living in villages in northern and central Rakhine State, internment camps in Sittwe, Kyauktaw, Kyaukphyu, Pauktaw and Myebon townships, and in Aung Mingalar quarter in Sittwe town. Those living in villages can generally travel to contiguous Rohingya or Muslim settlements within their village tracts but require a Village Departure Certificate (Tauk Kan Sa) to travel to other village tracts and Form 4s to travel beyond their township (depending on documentation status). Those living in isolated villages in central Rakhine State face perhaps the worst conditions, with extremely limited access to services or ability to travel. Most of the estimated 128,000 Rohingya displaced since 2012 remain confined to internment camps; they can generally move within their immediate camp areas but are proscribed from leaving the camps without permissions. Residents of camps which have officially been “closed” by the government have in some cases been afforded greater freedom of movement within areas proximate to their camps, but still cannot travel to their respective township centres or to other townships without permissions.

Recent changes by the government have allowed for greater movement by holders of the National Verification Card (NVC) in the northern Rakhine State townships of Buthidaung and Maungdaw, with those Rohingya who hold NVCs reporting notable decreases in extortion at checkpoints and permissions needed to travel within their own township or to their neighbouring township. However, NVC-holders in northern Rakhine State are still required to obtain Form 4s to travel to other townships or outside of Rakhine State, and NVC-holders in central Rakhine State (excluding Myebon Township) did not report improvements in their movement abilities.

More importantly, restrictions on movement have increased for the vast majority of Rohingya who do not possess an NVC or CSC. Movement abilities that were previously afforded to Rohingya, including the ability to apply for Form 4s or to go fishing, now require the card which is deeply unpopular within the Rohingya community because it is perceived as a marker of foreignness. As the government has ramped up efforts to enrol – and coerce – Rohingya into the card scheme, Rohingya face an impossible choice between societal stigma for accepting the card and heightened vulnerability if they reject it. While the government claims that the card is a legitimate response to the need to provide legal identity to hundreds of thousands of undocumented persons, the imposition of the NVC ignores the deep mistrust of government felt by the Rohingya following successive stages of disenfranchisement in which their previous identity cards have been revoked. That the government routinely forces people to take the NVC against their will reinforces suspicions among Rohingya that the card should not be trusted.

“For Rakhine young men from conflict-affected areas have only two options that whether they go to join with AA or leaving other places. We don’t have many choices.” Rakhine, now living in Malaysia

Conflict-affected Rakhine Communities

The escalation of fighting between the Arakan Army and Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) since late 2018 has upended historical movement dynamics in the state. While restrictions such as curfews and use of Village Departure Certificates in central and northern Rakhine State had previously targeted Rohingya and to a lesser degree Kaman, they have since been extended to affect all communities in conflict-affected parts of the state. While there are legitimate security concerns that may warrant the limited application of such measures, the way these restrictions have been enforced have raised concerns about human rights violations, arbitrary arrests and blocked access to services.

For Rakhine communities, the escalation of conflict between the Arakan Army and the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) since late 2018 and increased deployment of state security forces has become a key determinant of their ability to move freely. As of February 2020, more than 50,000 people have been displaced as a result of intense fighting across northern and central Rakhine State townships, with many unable to return to their homes or access their livelihoods. Non-displaced Rakhine living in areas affected by conflict have been required by Tatmadaw personnel to provide recommendation letters from their Village Administrators to traverse checkpoints, and in order to access medical care. Failure to observe strict curfews imposed by state security forces under Section 144 of the Myanmar Code of Criminal Procedure can lead to arrest and even violence. The conflict has had a particularly gendered impact on young Rakhine men, with many fleeing their villages upon the approach of Tatmadaw soldiers and avoiding checkpoints for fear of arbitrary arrest.

“When we are inside the pagoda/monastery together with them, we have fear because we are generally discriminated against. This is because our face looks like Muslim. We are really Buddhist, but we look like Muslim and speak like Muslims.” Maramagyi, Mrauk U Township

Kaman, Hindu and Maramagyi Communities

Other ethnic minority communities in Rakhine State are also living with restrictions on their freedom of movement. The predominantly Muslim Kaman community – recognised as citizens of Myanmar under the 1982 Citizenship Law – continue to face restrictions on their movement within Rakhine State, even if they possess CSCs. While Kaman are generally more likely to have access to citizenship than Rohingya, there are many within the community who lack the necessary documentation to officially apply for CSCs and who have instead been forced to accept NVCs. Regardless of documentation status, Kaman can face discrimination at checkpoints staffed by state security forces as a result of their racial characteristics and religious identity. Kaman in central Rakhine State are also required to obtain security escorts to travel to township centres and hospitals. The treatment of Kaman can vary depending on their geographic locale, with those located in central Rakhine State townships of Myebon and Sittwe facing greater restrictions than those in the southern Rakhine State township of Thandwe.

Hindu communities living in Maungdaw Township who do not possess CSCs are required to provide Village Departure Certificates or to inform their Village Administrator if they plan to travel overnight or outside of Maungdaw Township. Those without citizenship documentation are also required to obtain NVCs. Like others in conflict-affected areas, Hindus are now subject to curfews and Village Departure Certificate requirements.

Although generally facing fewer restrictions on their movement, Maramagyi communities in Mrauk U Township have also been required to inform their Village Administrator and in some cases obtain permissions to travel. As with Hindu communities in Maungdaw and Buthidaung townships, if Maramagyi are able to show documentation – most often Citizenship Scrutiny Cards – at checkpoints, they are able to move with relative ease.

“When a person has to move with an emergency at night, we actually need to pay the police at the checkpoint or they don’t allow to cross and go for also emergency issue even. For example, when a patient is taken to the clinic at night, we are not allowed to go without paying them. If we can give some charges, we can go to the clinic with the patient.” Kaman, Sittwe Township

COMMUNITY EXPERIENCES OF INFORMAL RESTRICTIONS

Informal, non-administrative restrictions on movement resulting from the wider socio-political factors also play a major role in determining the ability of individuals and communities to move. Three factors play a particularly large role in influencing movement “decisions”: the intercommunal policing of movement; a climate of impunity for perpetrators of human rights violations; and the failure of the government to ensure an environment of security. The interplay of these three factors, combined with the many formal restrictions on movement, create an environment of fear in which individuals and communities feel they have no choice except to limit their own movement.

Kaman, Maramagyi and Rohingya communities reported a fear of encountering Rakhine and the possible violence that might ensue as a major factor for restricting their own movement. Hard-line Rakhine and in some cases Hindu villagers often use violence or the threat of violence to intimidate other ethnic groups from traveling in their respective areas. These hardliners are enabled by a climate of impunity that has allowed perpetrators of human rights violations and civilians who block movement to escape accountability, furthering the perception among other ethnic groups that those who commit crimes against them will not be punished. Rather than ensuring their right to move freely, the government has instead further restricted the movement of ethnic minorities, claiming that it is unable to ensure their safety when travelling.

“We have a school in our village tract, but we are not allowed to study because the elders want to avoid the problem between Rakhine and Muslims in the school… The school is about a half mile away, and the children cannot use the main road because the [Rakhine] people throw stones and empty bottles at the students, when they are using the main road.” Rohingya, Minbya Township

IMPACTS OF MOVEMENT RESTRICTIONS

Arguably the most severe impacts of restrictions on freedom of movement result from communities’ consequent lack of access to healthcare. Although the location of communities is a significant variable, formal curfews and permissions requirements regularly preclude Rohingya, Kaman, Maramagyi, and Rakhine communities from accessing healthcare, in some cases resulting in avoidable deaths. Maramagyi and Rakhine communities living in Mrauk U, Buthidaung and Rathedaung townships face obstacles in accessing healthcare at night as a result of curfews, even in emergency cases.

For Rohingya and some Kaman, accessing healthcare can require a combination of Village Departure Certificates, Form 4s, medical referrals, security escorts, and/or bribes to state security forces staffing checkpoints on their journey. In the central Rakhine State townships of Kyauktaw, Mrauk U, Minbya, Myebon and Pauktaw, access to township hospitals is blocked by blanket bans on Muslims entering township centres, forcing Rohingya and Kaman to seek care at more limited station hospitals or costly trips to Sittwe General Hospital. The extreme difficulty of obtaining permissions for and cost of inter-township travel, especially in urgent cases, means that for Rohingya in northern Rakhine State access to tertiary healthcare is virtually non-existent.

Although variation exists among communities depending on their location, access to education for Rohingya, Kaman and Rakhine communities has likewise been limited by both administrative and non-administrative restrictions on movement. Conflict between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw has resulted in school closures, teacher shortages, and Rakhine communities being afraid to send their children to schools in areas affected by conflict. Kaman communities in Thandwe and Sittwe townships told the IRI that their absence of documentation or state-imposed restrictions was limiting their access to secondary and tertiary education in the state.

Restrictions on Rohingya communities’ access to education vary; those in northern Rakhine reported ease of access to primary and secondary schools, while those living in camps had more limited access to government schools, forcing a greater dependence on limited humanitarian-run temporary learning classrooms. Children in some isolated Rohingya villages in central Rakhine State have no access to government education and must instead attend community-run schools. Rakhine State’s universities continue to uphold a blanket ban on Muslim students, severely limiting tertiary education options for Rakhine and Kaman communities.

Livelihoods opportunities are limited across all communities in Rakhine State – Myanmar’s second-most economically impoverished State – and are further strained by government-imposed restrictions on movement, specifically in the farming and fisheries industries. For Rohingya fishermen, NVC requirements to obtain fishing licenses coupled with formal curfews have been devastating. Similarly, for Kaman communities in Sittwe Township restrictions on movement have significantly diminished their access to livelihoods. For both Rakhine and Maramagyi communities, conflict between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw has prevented individuals from travelling for work or accessing their fields and livestock. The compound effect of these government-imposed restrictions is to dramatically reduce household income, and further impoverish some of the most economically marginalised communities in Myanmar.

Instead of preserving ‘security’, restrictions on freedom of movement have in many cases precluded substantive improvements to intercommunal relations. Physical barriers such as fences and checkpoints that segregate populations and perceptions of insecurity arising out of a climate of impunity create an environment of fear of the other, reducing opportunities for intercommunal engagement and dimming prospects for social cohesion. Despite these challenges, interactions between communities continue throughout the state. IRI’s evidence suggests that areas with strong bonds between community leaders can facilitate freedom of movement at a local level and decrease the risk of the conflict. It is necessary to note, however, that these interactions continue to take place in an environment of structural discrimination against the Rohingya.

“In the past we have only one kind of travel constraint – now we have two kinds of travel constraint. We are also too afraid of the AA and Government. In the beginning the government together with the Rakhine people gave trouble to us. Now the conflict between them has started so now we are squeezed by both majority. Now Rakhine people come and we cannot recognise them – if they ask for money we don’t know if they are Rakhine, AA or Government. There is no rule of law anymore.” Rohingya, Minbya Township

MOVING FORWARD

This report finds that movement restrictions are pervasive and affect every community in Rakhine State. While a limited number of these restrictions may be justified given the increased security environment, most are arbitrary and necessitate revision and removal. The restrictions imposed on the Rohingya community are particularly problematic; resolving them requires not only lifting requirements for Village Departure Certificates and Form 4s, but broader reform of the structural causes that have led to the disenfranchisement and ostracization of the Rohingya community. But while addressing the plight of the Rohingya is critical, the framework provided by this report’s analysis indicates that structural discrimination affects multiple communities. To ensure that the right to freedom of movement is respected, protected and fulfilled, the Government of Myanmar has a responsibility to ensure that all communities have freedom of movement regardless of religion, ethnicity or citizenship status, lift arbitrary restrictions on movement, ensure accountability for those who abuse human rights and prevent others from moving, and provide a secure environment where individuals from all communities feel free and safe to move.

Accompanying this report is a Roadmap for Lifting Movement Restrictions in Rakhine State. This roadmap, based on the evidence provided by this study as well as relevant reports by other national and international organizations, is meant to serve as a platform for constructive engagement on an issue of critical importance.

- Remove all freedom of movement barriers related to attending schools or accessing education.

- Ensure that all communities can move freely for healthcare, including being able to access every healthcare facility in Rakhine State.

- Remove all freedom of movement barriers related to accessing livelihoods.

- Remove/modify movement permission and documentation requirements that infringe on communities’ rights to freedom of movement in Rakhine State, including the Form 4 and the Village Departure Certificate.

- Map existing policies and government regulations and their impact on freedom of movement.

- Remove unnecessary government-imposed barriers to freedom of movement unduly justified as security.

- Ensure the fair application of the rule of law by addressing accountability and extortion.

- Deconstruct apartheid conditions by desegregating communities and building social cohesion.

- Delink citizenship from freedom of movement and ensure restrictions are lifted for all regardless of citizenship status, religion or ethnicity, while also making changes to identity documentation and reforms to laws and processes to ensure access to greater access to citizenship.

To access IRI’s full findings

To access the recommendations

To see the recommendations in matrix form

About the Independent Rakhine Initiative

The Independent Rakhine Initiative is an interagency INGO project focused on building an evidence base for advocacy on rights issues in Rakhine State, Myanmar. Our goal is to increase access to essential services for Rakhine, Rohingya and other communities across Rakhine State. IRI is based in Sittwe and Yangon, Myanmar.

The views represented in IRI’s reports are those of the project only. IRI does not purport to represent the views or opinions of the INGO community or its partners.

Loading...

Loading...