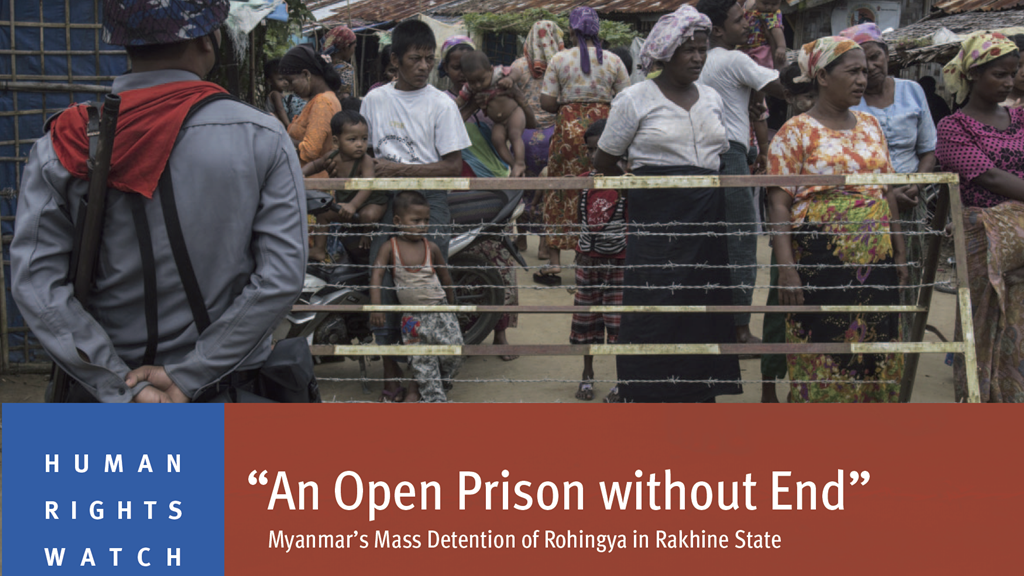

HRW Report: ‘An Open Prison without End: Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State’

- 08/10/2020

- 0

By Human Rights Watch

Summary

We have nothing called freedom.

–Mohammed Siddiq, lived in Sin Tet Maw camp in Pauktaw, September 2020

Download full report:

Loading...

Loading...

Hamida Begum was born in Kyaukpyu, a coastal town in Myanmar’s western Rakhine State, in a neighborhood where Rohingya Muslims, Kaman Muslims, and Rakhine Buddhists once lived together. Now, at age 50, she recalls the relative freedom of her childhood: “Forty years ago, there were no restrictions in my village. But after 1982, the Myanmar authorities started giving us new [identity] cards and began imposing so many restrictions.”

In 1982, Myanmar’s then-military government adopted a new Citizenship Law, effectively denying Rohingya citizenship and rendering them stateless. Their identity cards were collected and declared invalid, replaced by a succession of increasingly restrictive and regulated IDs.

Hamida found growing discrimination in her ward of Paik Seik, where she had begun working as an assistant for local fishermen. It was during those years a book was published in Myanmar, Fear of Extinction of the Race, cautioning the country’s Buddhist majority to keep their distance from Muslims and boycott their shops. “If we are not careful,” the anonymous author wrote, “it is certain that the whole country will be swallowed by the Muslim kalars,” using a racist term for Muslims.

This anti-Muslim narrative would find a resurgence years later. “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction but another race will,” became the motto of the Ministry of Immigration and Population. By 2012, a targeted campaign of hate and dehumanization against the Rohingya, led by Buddhist nationalists and stoked by the military, was underway across Rakhine State, laying the groundwork for the deadly violence that would erupt in June that year.

Hamida’s ward was spared the first wave of violence, but tensions grew over the months that followed. Pamphlets were distributed calling for the Rohingya to be forced out of Myanmar. Local Rakhine officials held meetings discussing how to drive Muslims from the town.

In late October 2012, violence returned. Mobs of ethnic Rakhine descended on the local Rohingya and Kaman with machetes, spears, and petroleum bombs. In Hamida’s ward, Rakhine villagers, often alongside police and soldiers, burned Muslim homes, destroyed mosques, and looted property. “The Buddhist people started attacking us and our houses,” Hamida recalls. “When we Muslims tried to protest and stand against the mob, the Myanmar security forces opened fire on us.” Soldiers shot at Rohingya and Kaman villagers gathered near a mosque, killing 10, including a child.

Hamida and her Muslim neighbors attempted to flee to Bangladesh. They arranged boats and set off at night. “We were on the Bay of Bengal for three days without any food,” she says. “When we arrived at the Bangladesh sea border, the authorities there provided us with some dry food—then pushed us back toward Myanmar.”

Hearing they could receive much needed food and aid at the camps in Sittwe, the Rakhine State capital, Hamida and her family made their way to Thet Kae Pyin camp. She lived there for six years with her husband and six children, first in a temporary settlement, later a shared longhouse shelter. Life in the camps brought hopelessness, fear, and pain.

“There is no future there,” Hamida says. “Do you think only tube wells and shelters inside the camp is enough to live our lives? We couldn’t go to market to get the items we needed, couldn’t eat properly, couldn’t move freely anywhere. We were in turmoil 24 hours a day.”

They were not allowed to study, work, or leave the camp confines. Hamida was unable to get the health care she needed.

“When our children died from lack of medical treatment, we had to bury them without any funeral,” she says.

In 2018, two of Hamida’s sons who had escaped to Malaysia spent 1,400,000 kyat (US$960) to send her and two of her daughters to Bangladesh. She sought medical care and the basic freedoms that her family had been denied for years. She now lives in another camp among nearly one million Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar. Her husband and two other children remain in Thet Kae Pyin, their requests to return home denied. She hopes one day they can all live in Kyaukpyu again. But only if they will be safe and free:

We want justice. We want to get back to our land. I have a desire to go back to my birthplace in Kyaukpyu before I die; otherwise, it’s better to die here in Bangladesh. Even the animals like dogs, foxes, or other creatures in the forest have their own land, but we Rohingya don’t have any place—although we had our own place once.

* * *

The 2012 coordinated attacks on Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State by ethnic Rakhine, local officials, and state security forces ultimately displaced over 140,000 people. More than 130,000 Muslims—mostly Rohingya, as well as a few thousand Kaman—remain confined in camps in central Rakhine State that are effectively open-air detention facilities, where they are held arbitrarily and indefinitely.

Many Rohingya told Human Rights Watch that their lives in the camps are like living under house arrest every day. They are denied freedom of movement, dignity, and access to employment and education, without adequate provision of food, water, health care, or sanitation.

The Myanmar government’s system of discriminatory laws and policies that render the Rohingya in Rakhine State a permanent underclass because of their ethnicity and religion amounts to apartheid in violation of international law. The officials responsible for their situation should be appropriately prosecuted for the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

The 2012 attacks on the Rohingya ushered in an era of increased oppression that laid the groundwork for more brutal and organized military crackdowns in 2016 and 2017. In August 2017, following attacks by an ethnic Rohingya armed group, security forces launched a campaign of mass atrocities, including killings, rape, and widespread arson, against Rohingya in northern Rakhine State that forced more than 700,000 to flee across the border into Bangladesh. While these atrocities, which amount to crimes against humanity and possibly genocide, have drawn international attention, the Rohingya who remain in Rakhine State, effectively detained under conditions of apartheid, have been largely ignored.

After the 2012 violence, the Rakhine State government segregated the displaced Muslims and ethnic Rakhine in Sittwe township in an ostensible effort to defuse tensions. While the displaced ethnic Rakhine have since returned to their homes or resettled, the government has maintained the Rohingya’s confinement and segregation for eight years.

Myanmar has failed to articulate any legitimate rationale for this extensive, unlawful internment. While the Rohingya have faced decades of systematic repression, discrimination, and violence under successive Myanmar governments, the 2012 violence provided a pretext for a longer term approach. “What they did in 2012 was overwhelm the Rohingya population,” said a UN officer who worked in Rakhine State at the time. “Corner them, fence them, confine the ‘enemy.’”

Rohingya in the camps are denied freedom of movement through overlapping systems of restrictions—formal policies and local orders, informal and ad hoc practices, checkpoints and barbed-wire fencing, and a widespread system of extortion that makes travel financially and logistically prohibitive.

Myanmar authorities meanwhile have enabled a culture of threats and violence that instills fear and self-imposed constraints. The central Rakhine camps violate international human rights law and contravene international standards on the treatment of internally displaced persons (IDPs), which provide that displaced populations “shall not be interned in or confined to a camp.” These violations are so severe that these camps cannot accurately be considered IDP camps at all, but rather open-air detention camps.

Access to and from the camps and movement within are heavily controlled by military and police checkpoints. Rohingya are not allowed to leave the camps without official, mostly unobtainable, permission. In the city of Sittwe, where about 75,000 Rohingya lived before 2012, only 4,000 remain. Surrounded by barbed wire, checkpoints, and armed police guards, they now live under effective lockdown in the last Muslim ghetto of Aung Mingalar.

The restrictions have given rise to a widespread system of bribes and extortion, while unauthorized attempts to leave result in arrest and ill-treatment. The constraints have tightened over the years. Mohammed Yunus lived in Ohn Taw Gyi camp in Sittwe before fleeing to Bangladesh. “During my years inside the camp, I saw the situation becoming more and more strict,” he said. “It was like an open prison without end.”

Myanmar officials have often invoked tensions between ethnic Rakhine and Muslim communities as the rationale for limiting Rohingya’s freedom to travel outside the camps. This claim is belied by the authorities’ involvement in stoking mistrust and fear and longstanding ability, demonstrated over decades of military dictatorship, to keep communal tensions in check.

The security risks posed at various points by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), the ethnic Rohingya armed group, and the Arakan Army, an ethnic Rakhine armed group, also fail to justify the repressive measures. The broad-based and harsh security restrictions imposed on Rohingya are unlawfully discriminatory, indefinite, and do not reflect specific security threats as international law requires.

The government’s policies have exacerbated the underlying ethnic tensions by failing to address hate speech and Buddhist nationalism, hold accountable perpetrators of violence, or promote tolerance. Instead of undertaking effective action to protect vulnerable communities, government officials have echoed and endorsed the threats, discrimination, and violence against the Muslim population.

A Rohingya woman from Aung Mingalar described her frustration with the government’s pretense: “They say, ‘Because of your security you can’t go outside [the camps].’ What security? If they wanted to put people in prison, they could. If they wanted to control the situation now, they could.”

Living conditions in the 24 camps and camp-like settings are squalid, described in 2018 as “beyond the dignity of any people” by then-United Nations Assistant Secretary-General Ursula Mueller. Severe limitations on access to livelihoods, education, health care, and adequate food or shelter have been compounded by increasing government constraints on humanitarian aid, which Rohingya are dependent on for survival. Fighting between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army since January 2019 has triggered new aid blockages across Rakhine State.

Camp shelters, originally built to last just two years, have deteriorated over eight monsoon seasons. The national and Rakhine State governments have refused to allocate adequate space or suitable land for the camps’ construction and maintenance, leading to pervasive overcrowding, high vulnerability to flood and fire, and uninhabitable conditions by humanitarian standards.

A UN official described her visit to the camps: “The first thing you notice when you reach the camps is the stomach-churning stench. Parts of the camps are literally cesspools. Shelters teeter on stilts above garbage and excrement. In one camp, the pond where people draw water from is separated by a low mud wall from the sewage.”

These conditions are a direct cause of increased morbidity and mortality in the camps. Rohingya face higher rates of malnutrition, waterborne illnesses, and child and maternal deaths than their Rakhine neighbors. An assessment of health data by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a humanitarian organization working in the camps, found that tuberculosis rates are nine times higher in the camps than in the surrounding Rakhine villages.

Lack of access to emergency medical assistance, particularly in pregnancy-related cases, has led to preventable deaths. Only 7 percent of live births took place in health facilities during the first quarter of 2018, putting mothers and newborns in life-threatening risk. Child mortality rates are also high. During a 10-day period in January 2019, five children under 2 died from treatable diarrheal illness.

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the extreme vulnerability in which Rohingya live. They face threats from overcrowding, aid blockages, and movement restrictions that increase the risk of transmission, as well as harassment, extortion, and hate speech from authorities.

Rohingya children are denied their right to quality education without discrimination. About 70 percent of the 120,000 school-age Muslim children in central Rakhine camps and villages are out of school. Given the movement restrictions, most can only attend under-resourced temporary learning centers led by volunteer teachers. The only high school in central Rakhine State open to Muslims, located in the Sittwe camp area, has just 600 students and a 100:1 student-teacher ratio.

Rohingya have been barred from attending Sittwe University since 2012 for undefined “security” reasons. A Rohingya woman who passed the matriculation exam to study in Yangon in 2005 but was never granted permission to leave Rakhine said: “Since childhood, I have lost many opportunities for my education. If I could have come [to Yangon] in 2005, I could have changed my life.” In one camp, only 3 percent of women are literate.

This deprivation of education is a violation of the fundamental rights of the 65,000 children living in the camps. It serves as a tool of long-term marginalization and segregation of the Rohingya, cutting off younger generations from a future of self-reliance and dignity, as well as the ability to reintegrate into the broader community. It also feeds into the cycle of worsening conditions and services. Without opportunities for Rohingya to study to become teachers or healthcare workers, the community is left with a growing lack of trained service providers, particularly as ethnic Rakhine are often unwilling to work in the camps.

Restrictions that prevent Rohingya from working outside the camps have had serious economic consequences. Almost all Rohingya in the camps were forced to abandon their pre-2012 trades and occupations. Former teachers and shopkeepers have been left seeking ad hoc and inconsistent work as day laborers for an average of 3,000 kyat (US$2) a day. An 18-year-old from Say Tha Mar Gyi camp said: “Some of us want to run our own businesses but we don’t have money to invest. Some of us want to be carpenters but we don’t have tools. Some of us want to go fishing but we don’t have boats.”

The seeming unending joblessness is a significant push factor in Rohingya seeking high-risk avenues of escape from the camps. Since 2012, more than 100,000 have willingly faced the threat of drowning at sea or abuse by traffickers to seek protection and the chance for a new life and work in Malaysia and elsewhere. A Rohingya woman explained: “We know we will die in the sea. If we reach there, we will be lucky; if we die, it is okay because we have no future here.”

The National League for Democracy (NLD) government, under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, has repeatedly demonstrated its unwillingness to improve conditions for Rohingya since taking office in 2016 following a half century of military rule. A Rohingya woman who fled Rakhine State described the lack of political will:

After the 2015 elections [when the NLD won], they have hope in the camps. They think things will change. After one year, they realize the Lady [Suu Kyi] will not do anything for us. They flee again. They are hopeless. She really doesn’t care. If the government wanted to control the monks, hate speech, it could.… Daw Suu is always talking about rule of law. If she actually practiced rule of law, we would be okay.

Little seems likely to change with the upcoming November elections. Most Rohingya have been barred from running for office and stripped of their right to vote.

Rohingya living in the camps have consistently expressed their desire to return to their homes, villages, and land, a right that the government has long denied. As Myo Myint Oo from Nidin camp said: “We want to go back to our places of origin and work our jobs again and live again with our neighbors in peace, like before 2012. We want to live in a safe place with other people, permanently.”

No compensation or other form of reparation has been provided for lost lives, homes, or property. A Kaman Muslim community leader said: “Nobody has been able to return, nobody has been compensated. We keep asking, even still we are asking the government for our land.… The land is still empty, there are no buildings there. We are still asking.”

In response to recommendations in an interim report from the government-appointed Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, led by the late UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the government announced in April 2017 that it would begin closing the camps. Its approach, however, has entailed constructing permanent structures in the current camp locations, further entrenching segregation and denying the Rohingya the right to return to their land, reconstruct their homes, regain work, and reintegrate into Myanmar society, in violation of their fundamental rights.

As noted in a March 2019 memo by the UN-led Humanitarian Country Team:

The Humanitarian community recognizes that the activities undertaken by the Government thus far in the framework of its “camp closure” plan are contributing to the permanent segregation of Rohingya and Kaman IDPs, and have not provided any durable solutions for IDPs or improved their access to basic human rights.

In November 2019, the government adopted the “National Strategy on Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and Closure of IDP Camps,” which it claimed would provide sustainable solutions. Yet the steps undertaken thus far offer no sign of improving the “closure” process or having any positive impact on the lives of camp detainees. A UN official called the strategy development “just a smokescreen,” and a 2020 UN analysis concluded: “The implementation of the strategy, in of itself, will unlikely resolve the fundamental issues that led to the displacement crisis in Rakhine state.”

The camp “closures” being carried out fall far short of the safe and dignified solution to displacement called for under international standards. Rohingya and Kaman as well as humanitarian agencies report that in the three camps labeled “closed,” there has been no notable increase in freedom of movement or access to basic services.

“Nothing has changed,” a Rohingya man living in one of the “closed” camps said. “We have had individual shelters since August 2018, but everything else has stayed the same. We don’t have freedom of movement, and still have major challenges for livelihood, income, and health.”

The camp closure process has triggered the UN and humanitarian groups to reevaluate their approach to working in the camps. These agencies have a humanitarian mandate to assist wherever it is needed, and the needs of the Rohingya in the camps are vast. But working in the camps for eight years has increasingly threatened to make them complicit in what agency staff have determined to be a government effort at permanent segregation and deprivation. Many are questioning their engagement with a government and military that have threatened and manipulated their operations for years.

One UN officer said: “Do you really want to invest millions in making concentration camps better? That is the question we’re facing.… You are helping them become permanent detainees.”

An internal UN discussion note from September 2018 asserted that despite the humanitarian community’s efforts, “the only scenario that is unfolding before our eyes is the implementation of a policy of apartheid with the permanent segregation of all Muslims, the vast majority of whom are stateless Rohingya, in central Rakhine.”

After eight years of de facto detention, the sense of hopelessness among displaced Rohingya is pervasive, and only worsened by the meaningless assurances of camp closures. Not one Rohingya interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed a belief that their situation in the camps could improve, that their indefinite detention may end, or that their children could one day live, learn, and move freely. “How can we hope for the future?” said Ali Khan, who lives in a camp in Kyauktaw. “The local authorities could help us if they wanted things to improve, but they only neglect [us].”

“I think they won’t solve this problem,” a Rohingya woman who had escaped Rakhine State said of the government’s plan to close the camps. “I think the system is permanent. A long time ago they took our money. Nothing will change. It is only words.”

In September 2012, then-UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Tomás Ojea Quintana gave a prescient warning about the government’s plan:

The current separation of Muslim and Buddhist communities following the violence should not be maintained in the long term. In rebuilding towns and villages, Government authorities should pay equal attention to rebuilding trust and respect between communities.… A policy of integration, rather than separation and segregation, should be developed at the local and national levels as a priority.

Yet, rather than “rebuilding trust and respect,” the government has maintained the Rohingya’s confinement and segregation for eight years—while having since resettled or returned the thousands of displaced Rakhine Buddhists—exacerbating ethnic and religious discrimination with devastating impact.

The 1973 Apartheid Convention applies to “inhumane acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” Apartheid and persecution are also crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

As the term “racial group” has been defined under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racism (ICERD) and by ad hoc international criminal tribunals, the Rohingya, as an ethnic and religious group, should be considered a distinct racial group for purposes of the Apartheid Convention.

Myanmar government laws and policies on the Rohingya community, notably their long-term and indefinite confinement in camps and villages, and regime of restrictions on movement, citizenship, employment, housing, health care, and other fundamental rights, demonstrate an intent to maintain domination over them. The adoption of many of these practices into state regulations and official policies and their enforcement by state security forces shows an intent for this oppression to be systematic.

Specific inhumane acts applicable to the government’s apartheid system include denial of the right to liberty; infringement of freedom or dignity causing serious bodily or mental harm; and illegal imprisonment. Various governmental measures appear calculated to prevent members of the Rohingya population from participating in the political, social, and economic life of the country, and deny group members their rights to work, to education, to leave and to return to their country, to a nationality, and to freedom of movement and residence. The government has also imposed measures designed to divide the population along racial lines by the “creation of separate reserves and ghettos” for the Rohingya and the confiscation of property.

All of these acts are ongoing in Rakhine State and amount to a regime of apartheid against the Rohingya.

A Litmus Test for Returns

Nearly one million Rohingya refugees live in overcrowded, flood-prone camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, most of whom fled Myanmar after August 2017 to escape the military’s mass atrocities. Since November 2017, the Myanmar government has made claims about its readiness to repatriate Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh, yet authorities have shown no willingness to ensure safe, dignified, or voluntary returns.

The eight-year mistreatment and confinement of 130,000 Muslims in central Rakhine stands as a clear rebuttal of the government’s claims. In 2018, the government built “reception centers” and “transit camps” in northern Rakhine State to process and house future returnees that are surrounded by high barbed-wire perimeter fencing—a mirror image of the detention camps in central Rakhine. Such structures, constructed on land from which the Rohingya had fled, and which was burned and bulldozed in their wake, constitute the new physical infrastructure of discrimination and segregation.

If operationalized, these camps for returning refugees would invariably limit basic rights, segregate returnees from the rest of the population, and exacerbate discrimination. As Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, then-UN high commissioner for human rights, said in July 2018, the central Rakhine detention camps “provide an ominous indication of what can be expected for any Rohingya returning from Cox’s Bazar to Myanmar under current conditions.” The narrative of a safe and voluntary repatriation process will remain a fiction until the Myanmar government undertakes fundamental, demonstrable, and lasting reforms.

Despite pressure from authorities in both Bangladesh and Myanmar, no Rohingya have formally agreed to return. Rohingya refugees told Human Rights Watch that while they wish to go home to Myanmar eventually, current conditions make their return unsafe. Repatriation attempts undertaken by the Myanmar and Bangladesh governments in November 2018 and August 2019 were widely opposed. Refugees compiled a list of demands outlining their conditions for return, including guarantees of citizenship and security, as well as freedom for the Rohingya in the central Rakhine camps.

One refugee told Human Rights Watch:

They [Myanmar authorities] always abuse us in different ways. Why would we go back to that country to endure the same cycle of abuse? If we are recognized as Rohingya, given citizenship, our lands, and assurance of freedom of movement, then no one will need to send us back. We will go ourselves.

“We are losing hope here also,” said Ibrahim Rafiq, who fled to Bangladesh in 2017. “Our fate made us live this refugee life. Still, I have hope that one day we will be able to go back to our village to live with safety and security.”

Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are watching the central Rakhine camps closely, deeply aware of what they signal for their futures. “They’re in touch, they’re very informed,” a humanitarian aid worker based in Rakhine said. “And no one wants to go back.”

Most Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh from the central Rakhine camps still have family living there and have heard about the tightening restrictions. “My mom said the situation is worsening there day by day,” said Abdul Kadar, whose mother lives in Thae Chaung camp. “Once she tried to flee to Bangladesh but the boat engine died, so she had to turn back.”

“We know that thousands of Rohingya back in Myanmar are still in detention camps,” said a Rohingya refugee a few days before the August 2019 repatriation attempt was set to start. “If those people are released and return to their villages, then we’ll know it’s safe to return and we’ll go back home.”

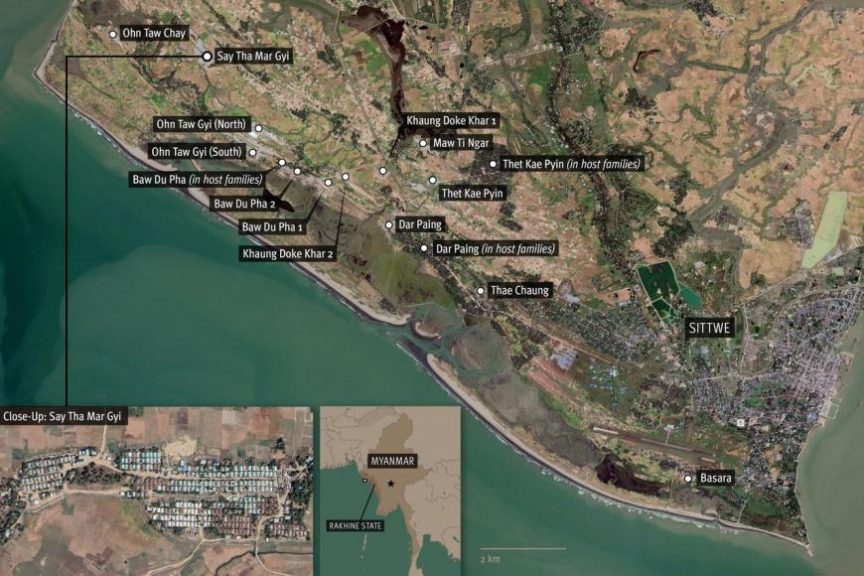

Rohingya and Kaman Camps in Central Rakhine State |

||

Township |

Camp name |

Population |

| Kyaukpyu | Kyauk Ta Lone** | 993 |

| Kyauktaw | Nidin* | 546 |

| Myebon | Taung Paw* | 2,920 |

| Pauktaw | Ah Nauk Ywe | 5,025 |

| Kyein Ni Pyin* | 6,091 | |

| Nget Chaung 1 | 4,786 | |

| Nget Chaung 2 | 4,759 | |

| Sin Tet Maw | 2,538 | |

| Sittwe | Basara** | 2,369 |

| Baw Du Pha (in host families) | 226 | |

| Baw Du Pha 1 | 4,697 | |

| Baw Du Pha 2 | 7,531 | |

| Dar Paing | 10,892 | |

| Dar Paing (in host families) | 2,951 | |

| Khaung Doke Khar 1** | 2,400 | |

| Khaung Doke Khar 2** | 2,234 | |

| Maw Ti Ngar** | 3,812 | |

| Ohn Taw Chay | 4,611 | |

| Ohn Taw Gyi (North) | 14,499 | |

| Ohn Taw Gyi (South) | 11,810 | |

| Say Tha Mar Gyi | 14,526 | |

| Thae Chaung | 12,380 | |

| Thet Kae Pyin** | 6,369 | |

| Thet Kae Pyin (in host families) | 2,942 | |

| Total population | 131,907 | |

| *Camps declared “closed” by the Myanmar government | ||

| **Camps identified for closure | ||

| Source: UNHCR and CCCM/Shelter/NFI Cluster Partners, June 2020 | ||

Key Recommendations

To the Myanmar Government

- End the laws, policies, and practices that have resulted in an apartheid regime against the Rohingya population.

- Lift all arbitrary restrictions on freedom of movement for Rohingya, Kaman, and other minorities, and cease all official and unofficial practices that restrict their movement and livelihoods.

- Respect the right of Rohingya to return voluntarily to their place of origin in safety and dignity, or to a place of choice, and to the return of their property.

- Halt the fundamentally flawed camp “closure” process in central Rakhine State and meaningfully engage Rohingya and Kaman communities, the UN, and international agencies to develop an updated strategy and implementation plan that ensures durable solutions, with clear timelines and procedures.

- Grant humanitarian groups and UN agencies immediate, unrestricted, and sustained access to Rakhine State.

- De-link ethnicity and citizenship, and citizenship and freedom of movement and other basic rights, so that these rights can be effectuated immediately, regardless of citizenship status or ethnicity.

- Rescind the 1982 Citizenship Law or amend it in line with international standards: ensure the law is not discriminatory in its purpose or effect, eliminate distinctions between different types of citizens, and use objective criteria to determine citizenship.

To the United Nations and Humanitarian Agencies

- Develop a comprehensive, practical, and detailed approach to assistance provision in Rakhine State, centered on long-term solutions for displaced populations that prioritize human rights protection and avoid reinforcing segregation, discrimination, and persecution of Rohingya.

- Urge the Myanmar government to halt the current camp “closure” process until thorough consultations with affected communities have been incorporated into an updated strategy, to be implemented in line with international standards.

- Develop a joint strategy for engaging publicly and privately with the government on Rakhine State, including establishing benchmarks for government progress on issues such as freedom of movement and access to health care. Failure to meet key asks should prompt groups to escalate collective advocacy and more broadly publicize the impact of the government’s discriminatory policies.

To Key International Governments and Donors

- Publicly and consistently press the Myanmar national and Rakhine State governments to end all policies and practices that promote discrimination, segregation, or unequal access to services.

- Condition funding for permanent infrastructure and development projects in Rakhine State on the government’s realization of human rights benchmarks, including the lifting of movement restrictions and other markers defined by the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State.

- Support international action to ensure accountability for grave crimes in Myanmar, including by urging the Security Council to refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court, and by urging Myanmar to take concrete steps to comply with the International Court of Justice’s provisional measures order directing Myanmar not to commit and to prevent genocide as part of Gambia’s case under the Genocide Convention.

- Impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on officials and entities—in particular, military-owned enterprises and companies—that are credibly implicated in grave international crimes, including apartheid and persecution.

- States party to the Apartheid Convention should investigate and prosecute, in accordance with article IV of the convention, those credibly alleged to be responsible for the crime of apartheid.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch in the city of Yangon and Rakhine State, Myanmar, and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, since late 2018.

We conducted interviews with 32 Rohingya living in the townships of Sittwe, Pauktaw, Myebon, Kyauktaw, and Kyaukpyu in central Rakhine State, and in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar who had fled the central Rakhine camps. Because Human Rights Watch is restricted by the Myanmar government from visiting the central Rakhine camps, all interviews with people detained there were conducted by phone.

Interviewees were informed how the information gathered would be used and that they could decline the interview or terminate it at any point. The majority of interviews were conducted directly in the Rohingya language. Some were conducted in Burmese with English interpretation. The names of Rohingya interviewees have been replaced with pseudonyms for their protection.

We also conducted more than 30 in-depth interviews with staff from United Nations agencies, international and local humanitarian organizations, and Rohingya and Kaman civil society groups, in addition to activists, community leaders, and local and regional analysts. Follow-up interviews were conducted over the phone and via other secure means of communications. Because of concerns of official backlash and security considerations, we have withheld the names and details of sources.

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch obtained, reviewed, and analyzed over 100 internal and public government, UN, and academic documents and reports related to the situation in central Rakhine State.

A Note on Terminology

In this report, the Rohingya camps in central Rakhine State are not referred to as the commonly used “internally displaced persons camps.” The use of the term internally displaced persons or IDPs to refer to the camp population obscures the government’s intent and minimizes its violation of international law, an illustration of authorities’ efforts to legitimize their repression of the Rohingya population. The term “detention camps” more accurately reflects the extreme movement restrictions imposed on the Rohingya since 2012 that amount to arbitrary and indefinite detention and severe deprivation of liberty.[1]

I. A History of State Violence and Abuse

Large-scale ethnically motivated attacks against the Rohingya have occurred repeatedly since Myanmar’s independence in 1948. In 1978, the Myanmar military drove over 200,000 Rohingya out of the country in a campaign of killings, rape, and arson. Another anti-Rohingya campaign followed in 1991-1992 that forced over 250,000 to flee to Bangladesh.[2]

Between 1993-1997, about 230,000 were forced back from Bangladesh to Myanmar—to northern Rakhine State, where the government sought to concentrate the Rohingya away from predominantly ethnic Rakhine parts of the state, subjecting them to increasingly restrictive and discriminatory policies and practices including the effective denial of citizenship, forced labor, and arbitrary confiscation of property.[3]

2012 Ethnic Cleansing and Internment

In early June 2012, sectarian clashes erupted between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya in four townships in Rakhine State. When violence resumed in October that year, it engulfed nine more townships and became a coordinated campaign to forcibly relocate or remove the state’s Muslims.

While often portrayed as intercommunal, the violence against the Rohingya was planned and instigated by government officials and state security forces.[4] Months before the violence started, local Rakhine political party officials and senior Buddhist monks had begun a campaign to vilify the Rohingya population, depicting them as a threat to Rakhine State and Buddhism, denying the existence of the Rohingya ethnicity, and calling for their removal from the country. A Rohingya woman living at the time in the city of Sittwe, Rakhine State’s capital, described the spread of propaganda: “Before the violence, they [Rakhine nationalists] were handing out pamphlets that said, ‘You need to wipe out these people or they’ll take your land.’”[5]

Immediately following the first wave of violence in June, local Buddhist monks circulated pamphlets calling for the isolation of Muslims. A Buddhist monk in Sittwe told Human Rights Watch in 2012:

This morning we handed our pamphlet out downtown [in Sittwe]. It is an announcement demanding that the Rakhine people must not sell anything to the Muslims or buy anything from them. The second point is the Rakhine people must not be friendly with the Muslim people. The reason for that is that the Muslim people are stealing our land, drinking our water, and killing our people. They are eating our rice and staying near our houses. So we will separate. We don’t want any connection to the Muslim people at all.[6]

Officials labeled Rohingya as “terrorists” who would take over the state with “uncontrollable” birth rates.[7] The Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (RNDP)—at the time the dominant party in the Rakhine State parliament, with an additional 14 seats in the national parliament—called on the national government to support its “endeavours to maintain the Rakhine race,” citing Adolf Hitler in its claim that “inhumane acts” are sometimes necessary:

The Union Government and the citizens collectively need to have a decisive stand on the issue of Bengali Muslims [Rohingya]. We cannot afford to waste time…. If we do not courageously solve these problems, which we have inherited from several previous generations … we will go down in history as cowards. For our citizens, for the maintenance of Buddhism, for the protection of our culture, it is now time to sacrifice.… Although Hitler and Eichmann were the greatest enemies of the Jews, they were probably heroes to the Germans.… If inhumane acts are sometimes permitted to maintain a race, a country and the sovereignty … our endeavours to maintain the Rakhine race and the sovereignty and longevity of the Union of Myanmar cannot be labelled as inhumane.[8]

The October 2012 attacks against Rohingya and Kaman Muslims were organized, instigated, and committed by local Rakhine political party operatives, the Buddhist monkhood, and Rakhine villagers, with active involvement of state security forces.[9] A Human Rights Watch investigation into the 2012 violence determined that the attacks were carried out with the intent to drive the Rohingya from the state or at least relocate them from areas in which they had been residing—particularly from areas shared with the majority Buddhist population.[10]

Hundreds of Rohingya men, women, and children were killed, some buried in mass graves, their villages and neighborhoods razed. State security forces frequently stood aside during attacks or directly supported the assailants, committing killings and other abuses. Human Rights Watch concluded that the atrocities amounted to crimes against humanity carried out as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing.[11]

Rohingya from central Rakhine describe 2012 as a turning point in the treatment of their community. Many Rohingya and Rakhine describe positive relationships and interactions between the communities prior to 2012. “I lived with my [Rakhine] neighbors for over 25 years,” said Myat Noe Khaing, a Rohingya woman who grew up in the city of Sittwe. “When the violence happened, they said, ‘We want to help you, but if we do, they will kill us too.’ Then everyday they started calling us ‘kalar.’”[12]

Khadija Khatun’s husband and son were killed when violence broke out in her town of Myebon in October 2012. “Police opened fire on the Rohingya who were fleeing,” she said. “My husband died. One of my sons died. When we were fleeing from our village, the Buddhist neighbors, who we were living together with for so many years, were swearing at us and saying they wanted to shower with our blood.”[13]

“For years, they’d lived next door without killing each other, depending on each other,” a UN official who worked in Rakhine State at the time said, describing the role that state forces had on instigating the violence. “It was engineered by the government, the military.… They used this conflict to advance their interests.”[14]

Over 140,000 people were ultimately displaced from their homes. In the wake of the violence, the Rakhine State government segregated the displaced Muslims and Buddhists in Sittwe township in an ostensible effort to defuse tensions. The long-term segregation, however, only resulted in worsening tensions and mistrust.

The government’s response to the 2012 violence—including its radically disparate treatment of the displaced Rohingya and the few thousand displaced Rakhine—indicated a calculated effort to capitalize on the crisis by segregating and confining a population it had previously sought to remove, with restrictions so harsh and unlivable as to spur their leaving the country.[15] RNDP leader Aye Maung laid out a plan for segregating the Rohingya just days after the June attacks: “We need to have a policy; an exclusive one, for these people and figure out how to defend this region—they will be repeatedly invading our territory.”[16]

Then-Myanmar President Thein Sein released an official statement in July 2012, one month after the first wave of violence, calling for Rohingya to be removed from Myanmar and seeking UN support to do so: “We will take care of our own ethnic nationalities, but Rohingyas who came to Burma illegally are not of our ethnic nationalities and we cannot accept them here.… The solution to this problem is that they can be settled in refugee camps managed by UNHCR [the UN High Commissioner for Refugees], and UNHCR provides for them. If there are countries that would accept them, they could be sent there.”[17]

“In 2012, things happened so quickly,” a humanitarian worker said, describing the beginning of the humanitarian response by the UN and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs). “The government was setting up internment camps, but no one noticed.”[18] Just a year later, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) warned in an internal situation update to the UN resident coordinator that the camps “are in effect manifestations of what is increasingly recognized as a de facto government policy of confinement.” The report added: “[the] restrictions on movement … may now arguably be impacting the right to life.”[19]

Post-Segregation Violence

The 2012 violence and ensuing displacement inflamed anti-Rohingya sentiment throughout Myanmar and precipitated an era of increased oppression, in both policy and practice, that became the groundwork for more brutal and organized military crackdowns in 2016 and 2017.

In October 2016, the ethnic armed group Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked three police outposts in northern Rakhine State.[20] The Myanmar security forces responded with months-long “clearance operations” against the Rohingya that involved extrajudicial killings, rape of women and girls, and the burning of at least 1,500 structures.[21]

In August 2017, following new ARSA attacks on police outposts, security forces again launched a systematic campaign of mass atrocities, including widespread killings, rape, and arson, against the Rohingya in northern Rakhine State. More than 700,000 were forced to flee to Bangladesh. In a September 2018 report, the Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, which the UN Human Rights Council had authorized in March 2017, asserted that evidence “suggests that the estimate of up to 10,000 deaths is conservative.”[22] The mission concluded on the finding of genocidal intent:

The actions of those who orchestrated the attacks on the Rohingya read as a veritable check-list: the systematic stripping of human rights, the dehumanizing narratives and rhetoric, the methodical planning, mass killing, mass displacement, mass fear, overwhelming levels of brutality, combined with the physical destruction of the home of the targeted population, in every sense and on every level.[23]

The Fact-Finding Mission called for senior military officials, including the military commander-in-chief, Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, to face investigation by an international criminal tribunal for alleged genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The Myanmar government has repeatedly denied that serious security force abuses took place, setting up successive investigations—none of which have been carried out credibly or impartially—to refute the extensive documentation of military atrocities.[24]

Most recently, it established an Independent Commission of Enquiry to investigate the August 2017 violence. The executive summary of the commission’s report, released in January 2020, contained selective admissions of military wrongdoing but failed to hold senior military officials responsible or provide a credible basis for justice and accountability.[25]

The National League for Democracy (NLD) government, under the leadership of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, has repeatedly proven unwilling to improve conditions for Rohingya in Myanmar or address the root causes of the crisis. A Rohingya woman who fled Rakhine State in 2013 described the lack of political will:

After the 2015 elections [when the NLD won], they have hope in the camps. They think things will change. After one year, they realize the Lady [Suu Kyi] will not do anything for us. They flee again. They are hopeless. She really doesn’t care. If the government wanted to control the monks, hate speech, it could.… Daw Suu is always talking about rule of law. If she actually practiced rule of law, we would be okay.[26]

The mass atrocities committed against the Rohingya in recent years have drawn international attention, while the Rohingya who remain trapped in villages and camps in Rakhine State—within a system of institutionalized oppression, under a military threateningly intent on “solving the [Rohingya] problem”—have been largely forgotten. As Ursula Mueller, then-UN assistant secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, stated after an April 2018 visit: “There is a humanitarian crisis on both sides of the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.”[27]

Since late 2018, fighting has escalated between the Myanmar military and Arakan Army, an armed group seeking greater autonomy for ethnic Rakhine. The armed conflict has increased insecurity across Rakhine State and displaced as many as 200,000 civilians in Rakhine and Chin States, the majority ethnic Rakhine.[28] Myanmar authorities responded by imposing new restrictions on aid, movement, media, and the internet. Hundreds of Rakhine and dozens of Rohingya civilians have been killed in the fighting.[29]

The Fact-Finding Mission has continued to raise concerns about the government’s treatment of Rohingya remaining in Rakhine State. In its September 2018 report, the mission found that the government’s systematic oppression of Rohingya may amount to the crime against humanity of apartheid as set out under the Apartheid Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: “The regime against the Rohingya is not a series of random occurrences but an overarching regimen of restrictions and abuses, that operate to cumulatively remove rights and erode the community’s dignity.… The ‘domination by one racial group over another’ has been accomplished.”[30] It further concluded that genocidal acts, including the imposition of conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction of the Rohingya group, had been committed.[31]

A year later, the Fact-Finding Mission reported that the Rohingya remaining in Rakhine State were still living under threat of genocide, concluding that “Myanmar is failing in its obligation to prevent genocide, to investigate genocide and to enact effective legislation criminalizing and punishing genocide.”[32]

In November 2019, Gambia filed a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) alleging that Myanmar’s atrocities against the Rohingya violate various provisions of the Genocide Convention.[33] In January 2020, the ICJ unanimously adopted Gambia’s request for “provisional measures.”[34]

The provisional measures require Myanmar to prevent all acts under article 2 of the Genocide Convention, ensure that its military does not commit genocide, and take effective measures to preserve evidence related to the underlying genocide case.[35] The court also ordered Myanmar to report on its implementation in May 2020, and then every six months afterward.[36] The order is legally binding on the parties.[37]

Although Myanmar is not a member of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the ICC ruled it has jurisdiction over the forced deportation of Rohingya because the crime was completed in Bangladesh, an ICC state party. In November 2019, the ICC authorized the investigation of alleged crimes against humanity committed against the Rohingya in Myanmar since October 2016, including forced deportation, persecution, and other inhumane acts.[38]

II. Citizenship and Identity

Am I wrong? For being Rohingya, being from Rakhine? I ask myself, what did I do wrong? But there is nothing wrong with me.

–A Rohingya woman from Aung Mingalar, April 2019

Rohingya Muslims have faced decades of systematic repression, discrimination, and violence under successive Myanmar governments. Central to their persecution is the 1982 Citizenship Law, which effectively denies them citizenship on discriminatory ethnic grounds.

In Myanmar, nationality is the principal link between the individual and the law: people invoke the protection of the state by virtue of their nationality. The Rohingya’s imposed statelessness has thus facilitated long-term and severe government human rights violations, including deportation, arbitrary confinement, and persecution. By linking ethnicity to citizenship, and citizenship to freedom of movement and other basic rights, the government has created a multilayered system of oppression.

In its September 2019 report, the Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar identified seven indicators of Myanmar’s genocidal intent against the Rohingya, including discriminatory policies such as the Citizenship Law and National Verification Card (NVC) process; derogatory and racist speech by Myanmar officials; and “the Government’s tolerance for public rhetoric of hatred and contempt for the Rohingya.”[39] Further, it took the government’s “failure to reform the Citizenship Law [and] the inhumane use of the NVC process” as evidence of continuing genocidal intent and ongoing, serious risk of genocide.[40]

In September 2016, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi created the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, chaired by the late UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, to “examine the complex challenges facing Rakhine State and to propose answers to those challenges.” Its final report released in August 2017 put forward 88 recommendations, including a call for a review of the Citizenship Law to eliminate the linkage between ethnicity and nationality and enable Rohingya to acquire citizenship.

The government at points asserted it had implemented 81 of the commission’s recommendations, a spurious claim—its progress has been superficial, limited, or nonexistent, particularly with regard to recommendations addressing critical human rights issues, including freedom of movement. Crucially, the government has wholly refused to address the issue of citizenship.[41]

Hate and Denial of Identity

The government’s persistent rights violations against the Rohingya have been facilitated by a long-term process of dehumanization and “othering.” The government, along with Myanmar society more broadly, openly considers the Rohingya to be illegal immigrants from what is now Bangladesh, and not a distinct “national race” under Myanmar law, despite the fact that many families have lived in Myanmar for generations, if not centuries.[42]

In its application at the International Court of Justice alleging Myanmar violated the Genocide Convention, Gambia cited as an indicator of genocidal intent the Myanmar authorities’ dehumanizing and hate-filled rhetoric toward the Rohingya.[43]

The Rohingya were excluded from the 2014 census—conducted in partnership with the UN Population Fund—denying their existence in the country and obstructing the collection of population and demographic figures.[44] A 60-year-old Rohingya man living in the Dar Paing camp in Sittwe said: “The census team asked me, ‘What is your ethnicity?’ When I answered ‘Rohingya,’ they walked away. They didn’t even ask me any of the other questions. Now if we don’t appear in the census, are we really here?”[45]

The government is overt in its erasure of the Rohingya identity. In a 2014 report to the UN, the Myanmar government stated: “The term ‘Rohingya’ has never existed in our national history.… The said term is maliciously used by a group of people with ulterior motives. The people of Myanmar never recognizes it.”[46] Official statements refer to the Rohingya as “Bengali” or “the Muslim community in Rakhine.”

Aung San Suu Kyi refuses to call the group “Rohingya” and told international stakeholders, including the United States, European Union, and UN, as well as the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, to follow suit.[47] Since Suu Kyi’s party took office in 2016, media groups have been pressured to cease using “Rohingya”; the authorities banned Radio Free Asia from broadcasting on local outlets after it refused to comply.[48]

All individuals in Myanmar, including the Rohingya, are entitled to a nationality and to self-identify in line with international human rights standards. As the Fact-Finding Mission noted, avoiding the use of the term Rohingya “feeds the narrative that the Rohingya do not belong in Myanmar … denies their right to self-identification, and contributes to their stigmatisation and marginalisation.”[49]

For Rohingya, their call for the right to self-identify is closely linked to other rights. Jamal Ullah from Ohn Taw Gyi camp said: “We want the name ‘Rohingya.’ We want our homes, we want our country. We want to get back the things we owned.”[50]

The 2012 violence was followed by a nationwide escalation of Islamophobia and the growing influence of Buddhist extremism in public and political spheres.[51] The military began training soldiers on protecting Buddhist Myanmar from the existential threat of Islam, with lectures warning that “the danger of being swallowed up by Bangladeshi Chittagonian ‘kowtow kalars’ truly exists.… They infiltrate the people to propagate their religion.”[52]

Buddhist nationalist groups including 969 and the Race and Religion Protection Association, or Ma Ba Tha, effectively tapped into the divisive ethno-religious nationalism that triggered the 2012 ethnic cleansing campaign in Rakhine State. These groups became increasingly influential alongside certain prominent Buddhist monks such as Wirathu, who held frequent public rallies to spread populist anti-Muslim propaganda.[53] In 2015, Ma Ba Tha successfully campaigned for the government to pass four discriminatory “race and religion protection laws,” marking a new level of sway over the Myanmar government.[54]

Similarly, the official rhetoric depicting Rohingya as illegal immigrants swelled after the August 2017 violence. Commander-in-Chief Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing posted a statement in September asserting, “So we openly declare that ‘absolutely, our country has no Rohingya race.’”[55] A spokesperson for the ruling NLD party responded to the international attention on Rakhine State, saying, “We ask the international community to acknowledge that these Muslims are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and that this crisis is an infringement of our sovereignty.”[56] A member of parliament expressed gratitude that so many Rohingya had fled: “All the Bengalis learn in their religious schools is to brutally kill and attack. It is impossible to live together in the future.”[57]

Military and government officials employ hate-filled language that both echoes and fuels the narrative of Buddhist extremist violence. A decade of statements from authorities endeavor to paint the Rohingya not only as less than Burmese, but less than human. They are commonly called “dogs,” “snakes,” and “fleas,” including by authorities and Buddhist leaders. A soldier deployed to Rakhine State in August 2017 posted on Facebook: “On the battlefield, whoever is quick will get to eat you, Muslim dogs.”[58]

In a book on the Rohingya published by the Myanmar armed forces’ Directorate of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare, the military wrote: “The origin and glory of a race cannot change. Despite living among peacocks, crows cannot become peacocks.”[59]

As the Fact-Finding Mission concluded, “their extreme vulnerability is a consequence of State policies and practices implemented over decades, steadily marginalising the Rohingya. The result is a continuing situation of severe, systemic and institutionalised oppression from birth to death.”[60]

A Rohingya woman who escaped the central Rakhine camps said she wonders about the fate she and her family have faced for simply being Rohingya: “Am I wrong? For being Rohingya, being from Rakhine? I ask myself, what did I do wrong? But there is nothing wrong with me.”[61]

Denial of Citizenship

Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law violates several fundamental principles of customary international law and Myanmar’s obligations under various human rights treaties, and leaves Rohingya exposed with no legal protection of their rights.

International law obligates states to avoid acts that would render stateless anyone who has a genuine and effective link to that state. Such a genuine and effective link can be determined by factors like long-term residence, family ties, descent, or birthplace.[62]

Promulgated soon after the mass return of Rohingya who fled in 1978, the Citizenship Law established a tiered, ethnic-based citizenship scheme. The use of ethnicity rather than objective criteria as a primary basis for granting citizenship violates international legal prohibitions on racial discrimination.[63] The law defines three categories of citizens: full citizens, associate citizens, and naturalized citizens. Color-coded Citizenship Scrutiny Cards are issued according to citizenship status—pink, blue, and green, respectively.[64] Each card records name, sex, religion, race, father’s name, and identification number.

Full citizens are members of one of the recognized “national ethnic groups” who settled in the country before 1823, the beginning of the British occupation, and whose parents also hold citizenship. The law names eight primary groups—Bamar (Burman), Chin, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, Mon, Rakhine, and Shan—but government officials have referenced a total of 135 recognized ethnic groups, which does not include the Rohingya, since around 1989. General Ne Win, Myanmar’s long-time military dictator, said shortly after the law was established: “This is not because we hate them. If we were to allow them to get into positions where they can decide the destiny of the state and if they were to betray us we would be in trouble.”[65]

Associate citizenship became available under the 1982 law for those whose citizenship applications under the prior law were pending in 1982. Persons can become naturalized citizens if they can provide “conclusive evidence” that they entered and resided in Myanmar prior to independence in 1948. Those who have at least one parent who holds one of the three types of citizenship are also eligible to become naturalized citizens. The law stipulates that naturalized citizen applicants must be at least 18 years old, be able to “speak well” one of the national languages, and be of “good character” and “sound mind.”

According to the terms of the law, only full and naturalized citizens are “entitled to enjoy the rights of a citizen under the law, with the exception from time to time of the rights stipulated by the State.” All forms of citizenship, “except a citizen by birth,” may be revoked by the state.[66] Most of the country’s ethnic minority populations, including those named in the law, were negatively impacted by its passage, which formalized the primacy of the majority Bamar.

Most Rohingya lack formal documents, even those whose families have lived in Myanmar for generations, leaving them with no means to provide “conclusive evidence” of their lineage in Burma prior to 1948, let alone prior to 1823. And although international human rights law ensures non-citizens virtually all the rights of citizens, except for the right to vote, the Myanmar government has long used the Rohingya’s absence of citizenship to deny them fundamental human rights. The 2008 Constitution further enshrines this violation by embedding citizenship as a prerequisite for enjoying constitutional rights.[67]

The difficulty for Rohingya of providing “conclusive evidence” of their lineage increased in 2012, when many lost their documents in arson attacks or had them forcibly taken. Several Rohingya told Human Rights Watch that during the June and October violence, local authorities or groups of ethnic Rakhine confiscated their ID cards.[68]

Under the 1982 law, the children born to non-citizens do not obtain citizenship, perpetuating the denial of citizenship to Rohingya over generations. In order for a child to obtain citizenship, at least one parent must already hold one of the three types of citizenship. In this respect, the Citizenship Law conflicts with the Myanmar government’s obligations under article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states, “The child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right to a name [and] the right to acquire a nationality.” It calls on states parties to ensure implementation of these rights “in particular where the child would otherwise be stateless.”[69] Myanmar ratified the convention in 1991 and is obligated to grant citizenship to children born in Myanmar who would otherwise be stateless.

Discrimination against Rohingya children begins at birth, with many denied legal recognition of a birth certificate, which in turn restricts them from accessing future opportunities to study, marry, or travel.

The practice of registering newborn Rohingya was informally phased out in the 1990s and sharply curtailed in 2012. The Advisory Commission on Rakhine State reported that “birth registration of [Rohingya] Muslim babies came to an almost complete halt after the violence in 2012,” and that “today, the majority of Muslim children … lack such documentation.”[70] Ko Min Kyaw, who lives in Ohn Taw Gyi camp, explained:

A lot of children born after June 2012 don’t have a record in the camp or host community. So, the local authorities and Rakhine State government are accusing them of being illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. The government, INGOs [international nongovernmental organizations], and the UN haven’t been able to solve this issue. It means a lot of people will be automatically stateless in the future.

Also, some of the children who applied for citizenship failed because they don’t have a birth certificate, [which is] a requirement of the citizenship application. This issue is very important and a big challenge for the Rohingya children in Rakhine State.[71]

In July 2019, the government passed a new Child Rights Law that states, “All children born within the country shall have the right to birth registration free of charge without any discrimination.”[72] However, it clarifies that children have the right to citizenship “in accordance with the provisions under the existing law,” perpetuating the 1982 Citizenship Law’s exclusion of Rohingya children.[73]

Aung San Suu Kyi’s office held a press conference on the law confirming that “the child’s citizenship will be determined by 1982 Citizenship Law … a non-citizen child will not become a citizen. A registration of a birth would not make the registered child a citizen.” The director-general of the State Counsellor’s office reported that birth certificates will have “written in red letter that this is not a certificate of citizenship.”[74]

National Verification Cards

Rohingya’s right to nationality has been steadily eroded over decades, with successive citizenship regimes increasingly restricting their access to identity documents. Documentation establishes a person’s legal identity, serving as the basis for accessing fundamental rights and services—education, employment, owning property, medical treatment, freedom of movement, and receiving state protection.[75] At several junctures, Rohingya were required to turn over their prior documentation to be replaced with a lesser identity card, or none at all.[76] “They say we are foreign settlers,” said one Rohingya man. “My grandfather had a citizenship card. My mother. My father. My older brother. But they say I am not a citizen.”[77]

Beginning in 1995, the government issued many Rohingya “white cards,” or temporary registration cards, which did not carry citizenship rights but did afford them the right to vote. However, the government nullified the white cards in 2015, disenfranchising the Rohingya ahead of the November 2015 national elections.[78]

Ahead of the November 2020 elections, the government seems again intent on suppressing Rohingya’s political rights. The election commission barred at least six Rohingya candidates from running. Six others were approved to run but expressed little optimism given their disenfranchised electorate. The voter lists posted around the country are absent from the Rohingya detention camps.[79] Sultan Ahmad from Thet Kae Pyin camp said:

We have big concerns about the coming election in 2020. In 2015, we lost the right to vote by the union government. It is not fair for Rohingya and Kaman. In 2020, the international community should advocate to the government to get us a chance to vote in a fair election for Rohingya.[80]

In 2014, the government began rolling out a coercive “citizenship verification” process in Rakhine State, launched in a Myebon camp, which required Rohingya to register as “Bengali.” After several stops and starts, Myanmar is once again pushing ahead with a revised National Verification Card system, an inherently discriminatory process that does not signify citizenship, but merely serves as another government tool of exclusion and control.[81]

The NVC process has been widely rejected by Rohingya, who see it as marking them as foreigners in their own land. “You take that card with that name, now you are not Rohingya, you are Bengali,” a Rohingya woman said.[82] Exemplifying such concerns, the NVC application form asks for the applicant’s date of entry into Myanmar and place of arrival. In a statement to the UN General Assembly, Union Minister Kyaw Tint Swe compared the NVC to the US “green card” for permanent residents.[83]

The government calls the NVC a “first step toward citizenship,” which is not true. The card itself notes that the holder is not a Myanmar citizen, but rather “a person who need to apply for citizenship in accordance with Myanmar Citizenship Law.” NVC-holders are still required to apply for citizenship and undergo verification in accordance with the 1982 Citizenship Law. Authorities allege the process takes six months, but Rohingya who have attempted it report their applications have faced up to two-year delays or remain unanswered.[84]

Few have been successful. Official reporting on NVC statistics has been inconsistent, but the government has made various claims of having issued between 13,000 and 16,000 NVCs in Rakhine State.[85] In one report, the union minister for social welfare, relief, and resettlement asserted that of 13,215 NVC recipients from Rakhine, 1,276 adults and children had been granted citizenship—about 0.2 percent of the 600,000 Rohingya left in Myanmar.[86] In its most recent update, the government’s Implementation Committee on Recommendations on Rakhine State reported that 1,144 NVCs and 46 citizenship cards were issued from September to December 2019.[87]

Rohingya report authorities using threats, violence, and coercion to force them to accept the NVC, including withholding access to lifesaving resources and increasing restrictions on movement as retribution for refusing to take the card.[88] Prior to the August 2017 violence, officials made statements at meetings with Rohingya threatening to kill or harm them if they refused to accept the NVC.[89] Hundreds of Rohingya who were released from prison as part of an April 2020 amnesty were forced to accept NVCs before returning to Rakhine State.[90]

The card is positioned as a prerequisite for accessing livelihoods such as fishing or working for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the camps, and for receiving various services such as food assistance, raising serious concerns about its voluntary and secure nature.[91] Rohingya describe authorities telling them: “If you want to move, you need to take these cards.”[92] Those who have been issued a card say they have not been granted meaningful freedom of movement, as promised by the government, while those who refuse have faced worsening constraints.

Abdul Kadar, 32, who lived in Thae Chaung camp until 2018 but never accepted the NVC, said:

After the 2012 violence, suddenly the government came up with the NVC card offer. Like they were offering us, if we would take the NVC then we would be given permission to work freely, move freely.… We could not do anything independently if we did not take the NVC. From 2016, the people who didn’t take the NVC were not even allowed to move anywhere, and the situation became more strict for us.[93]

Some Rohingya in northern Rakhine State who accepted NVCs reported slight decreases in local travel restrictions and extortion at checkpoints, though both remain ever-present factors. No such changes, however, were reported by NVC-holders in central Rakhine State. Rohingya with NVCs are still prevented from leaving the camps at night, and many have faced arrest while traveling, despite holding the card.[94]

Nurul Bashar, 25, fled to Cox’s Bazar in 2017 but still has family in Thae Chaung camp in Rakhine State. He said that the government’s promises of the freedoms the card would afford have proven false:

Last month [October 2019] when I talked to my family, they said they had taken the NVC cards after believing authorities’ promises that it would let them travel frequently to Yangon. But now they are not even allowed to stay in another Muslim village. People who have the NVC card, they can go for fishing but only for three days. Nothing changed after taking the NVC.[95]

Amir Hossain lived in Thet Kae Pyin camp in Rakhine State until 2018, where his family still lives. He said that security officials are increasing their efforts to pressure Rohingya in the camps to accept the NVC, adding that older Rohingya were being targeted in particular: “Authorities just called my father along with 30 other people to the police camp to take the NVC card. They are trying to force people to take the cards by calling the elders to the police camps to get the NVCs. Authorities think older Rohingya will take the cards because they are afraid.”[96]

Kamal Ahmad from Khaung Doke Khar camp said: “These days, the Myanmar authorities are forcing the Rohingya in the IDP camps to have NVC cards. Every day there are meetings called by authorities with the Rohingya [about the cards].”[97]

Many Rohingya in camps that have been declared “closed” or slated for closure have been forced to accept NVCs before moving houses, such as those in Myebon’s Taung Paw camp. Sandar Swe, who lives in Taung Paw, said: “The authorities started talking to us two years ago about applying for the NVC. We understand that it’s not very useful for us, but we didn’t want trouble with local authorities and the Rakhine State government, so a lot of people applied.”[98]

Rahim Iqbal also lives in Taung Paw, where he was moved to new housing under the camp’s “closure” process in 2018. He said that during the move:

The authorities also forced us to take NVC cards. The card labeled us “Bengali.”… With the NVC card, some Rohingya can travel to Sittwe [the state capital], but not freely. There are still restrictions on movement from one place to another place after the evening. We still cannot go outside the camp to go shopping or buy essentials or do any work—we are only allowed to work inside the camps.[99]

Rohingya’s concerns regarding the National Verification Cards have been borne out by authorities’ enforcement of the process. NVCs have failed to reduce statelessness or protect the rights of those marked by lack of citizenship. Instead, characterized by coercion and deceit, the NVC process has entrenched a discriminatory system and upheld the government’s long-standing use of identification systems as means of marginalization.

III. Restrictions on Freedom of Movement

The central Rakhine camps, where about one-quarter of the country’s remaining 600,000 Rohingya reside, exemplify the government’s repression and persecution of the group.[100]

The government-created Advisory Commission on Rakhine State noted in its final report in August 2017: “Freedom of movement is one of the most important issues hindering progress towards inter-communal harmony, economic growth and human development in Rakhine State.”[101] The commission called for the government to ensure freedom of movement for all people in Rakhine State, regardless of religion, ethnicity, or citizenship status.[102]

Open-Air Prisons

As of June 2020, an estimated 131,900 displaced Rohingya and Kaman resided in 24 camps or camp-like settings in five central Rakhine townships: Sittwe (16 sites), Pauktaw (5), Myebon (1), Kyaukpyu (1), and Kyauktaw (1). The population is primarily Rohingya, plus a few thousand Kaman Muslims. Over half of the displaced are under 18 years old. An estimated 75 percent are women and children.[103]

Rohingya in the camps are denied freedom of movement through overlapping systems of restriction—barbed-wire fencing, checkpoints, and other physical barriers; widespread extortion and bribes; restrictive and arbitrary permission procedures; denial of documentation; security force presence and abuse; and an environment of threats and violence that instills fear and self-imposed constraints.

These restrictions are carried out through formal government policies, written and oral local orders and regulations, and informal and ad hoc practices implemented by local authorities. Together, they serve to arbitrarily deprive Rohingya of their liberty and disproportionately limit their movement in violation of international law. In addition, the severe restrictions on movement sharply hinder their access to other rights, notably health care, livelihoods, shelter, and education. “Every day it is like we are under house arrest,” said Myo Myint Oo from Nidin camp in Kyauktaw.[104]

The Rakhine State government segregated the displaced Muslims and Buddhists in 2012. For displaced Rohingya in Sittwe township, a rural area was sealed off with barbed wire fencing and military checkpoints.[105] Nurul Bashar, 25, described the transformation of his village, Thae Chaung, into a militarized displacement site:

My village turned into an IDP camp…. Over those three months [after June 2012], the authorities imposed more restrictions on the people living in my village and the Rohingya taking shelter there. After the attacks, four new checkpoints were built in our area. Whenever we crossed the checkpoints, we had to walk bowing down our heads.[106]

Thae Chaung, a self-settled rather than planned camp, remains one of the largest central Rakhine camps, with an estimated 12,300 Rohingya.

Anwar Islam, 25, who also lived in Thae Chaung village in Sittwe at the time of the 2012 attacks, described the 2012 internment as an inflection point in their lives:

During childhood, I realized we were being discriminated against by Buddhists. At school they always swore at us, calling us “Bengali” and “kalar.” Security forces always stopped us and searched for something to fault. If they found anything, they would torture us. But still, we were able to travel. We Rohingya had businesses. Some Rohingya owned boats. We were free, at least.…

After 2012, Rohingya from other villages who were affected by the attacks took shelter in our village. The area turned into IDP camps. The whole place was locked down. We faced huge problems, restrictions imposed on us.… The camp is not a livable place for us Rohingya.[107]

Kamal Ahmad, 23, lived in Sittwe’s Khaung Doke Khar camp after fleeing his home in Na Zi ward, just a few kilometers away. He said: “After the violence happened in 2012, authorities started putting restrictions on our movement. Police patrolling in my area increased a lot.”[108]

Many Rohingya who were originally from areas not affected by violence also ended up living in the camps. Some were rounded up by security forces and forcibly relocated, some fled to the camps due to threats and fear. For others, the restrictions placed on them by authorities were so severe that the camps, where they could receive humanitarian assistance, seemed like a better option. Mohammed Yunus, 37, said:

I started living with my family in the IDP camp in December 2012. The area where I used to live [in Sittwe] was not affected by the June violence. But after the attacks, Myanmar authorities started putting so much restriction on our movement [in the city], prices of daily needs went up. At the same time, we were not allowed to do any work or business, so at some point I decided to go to the IDP camp.[109]

Local government officials forcibly displaced many Rohingya families after the violence in both June and October 2012, some from their homes and others from their first displacement sites. A Rohingya fisherman from Pauktaw described how his village was sent to Sittwe: