Repatriation Must be Voluntary, Safe and Dignified

- 19/08/2019

- 0

By Aman Ullah

Myanmar and Bangladesh are to make a fresh attempt to begin repatriating the Rohingya Muslims who fled ethnic cleansing in Rahkine state in 2017, though the community says they have not been consulted.

It is said that the move follows Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s recent visit to China and Japan, the two Myanmar’s close allies, who want a bilateral solution to the crisis.

Since August 25, about 700,000 Rohingyas have entered Bangladesh fleeing persecution in Myanmar, making Bangladesh the fourth largest host country for refugees. This is ever largest refugee crisis since WWII which Bangladesh, an over populated country, has now to face. Antonio Guterre, the UN Secretary General, termed it as “the world’s fastest developing refugee emergency”. The situation is so dire that the UN human-rights chief has called a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” while the rights bodies termed it as genocide and crime against humanity. A UN fact-finding mission declared the violence had “genocidal intent”.

In July, Myanmar officials went to the camps in Bangladesh to talk to the refugees about their plans and preparations to bring them back, in the latest of several similar visits. So far, most refugees appear to distrust the promises and believe it is too dangerous to return.

On July 30, Bangladesh handed a list of 25,000 Rohingyas of 6,000 families to a visiting Myanmar delegation during a meeting at the state guesthouse, Meghna. Bangladesh had earlier handed Myanmar lists of some 30,000 Rohingyas for verification of their identity, but only 8,000 of them were verified. Repatriation could not begin as scheduled on November 15 last year as the refugees refused to go.

Reuters reported yesterday that a total of 3,540 refugees have been cleared for return by Myanmar from a list of more than 22,000 names recently sent by Bangladesh, officials from both countries said. The first group of refugees would return to Myanmar on August 22, providing any agree to go back.

On November 23, 2017, Bangladesh hastily signed the deal with Myanmar in the first place and again on January 16. Though it is international crisis and UN has a mandatory role to find solution to such problem, no international organizations were involved in this deal.

The deal was not properly made and the refugee representatives were not allowed to participate. Even their demands had not been considered. The MOU provided for involvement of UNHCR on the Bangladesh side in the repatriation process.

The fate of the Rohingya repatriation deal was bound to falter from the beginning.

The repatriation was scheduled to start from January 23 as per the latest arrangement signed with Naypyitaw on January 16, but it did not start as officials pointed out incomplete process and a lot more need to be done to ensure safe return on voluntary basis. Bangladesh official said it has been delayed but virtually none can say when the process will complete; because the agreement with Myanmar can’t deliver the much needed guarantee in absence of guarantee for safety.

So the repatriation did not start on the stipulated date, but Myanmar government blamed Bangladesh for failing to start the repatriation. It said they have all preparations to receive the refugees; they have set up rehabilitation centers but it is Bangladesh government failed.

The fact is that despite the hurriedly signed agreement, Rohingyas are not willing to return to face the same persecution and the international community is equally supportive to Rohingyas denial to move to uncertain future once gains. Many of them returned to Rakhine state on earlier occasions only to be killed or flee again to Bangladesh to escape from the ethnic cleansing.

They want strong undertaking now from the Myanmar government and the international community about the restoration of their citizenship, right to free movement and access to health, education , livelihood and the most important thing- their security and safety in homeland. luntary repatriation agreement is problematic for four reasons. Firstly, Myanmar does not seem to have the political will to take back Rohingya refugees. It had agreed to sign the repatriation agreement simply under diplomatic pressure. Secondly, Rakhine is nowhere near safe for the Rohingya to return home. Anti-Muslim sentiment is deeply entrenched in the state. Thirdly, Myanmar is taking back people only if they are able to prove their residence and finally, there is still uncertainty on what extent is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) going to involved in the repatriation process.

This is the second attempt to begin repatriation, after a first effort in November failed when none of the 2,000 Rohingya approved for return agreed to go back to Myanmar voluntarily.

A document prepared by UN agency UNHCR to be sent to the Rohingya community to inform them of the repatriation plan said: “The Government of Myanmar has confirmed that 3,450 Rohingya refugees are eligible to return. This is a welcome first step as it acknowledges that your right to return is recognized.”

Caroline Gluck, a spokeswoman for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, told The Associated Press that the Bangladesh government has asked for its help in verifying 3,450 people who signed up for voluntary repatriation. She said the list was whittled down from 22,000 names that Bangladesh had sent to Myanmar for verification.

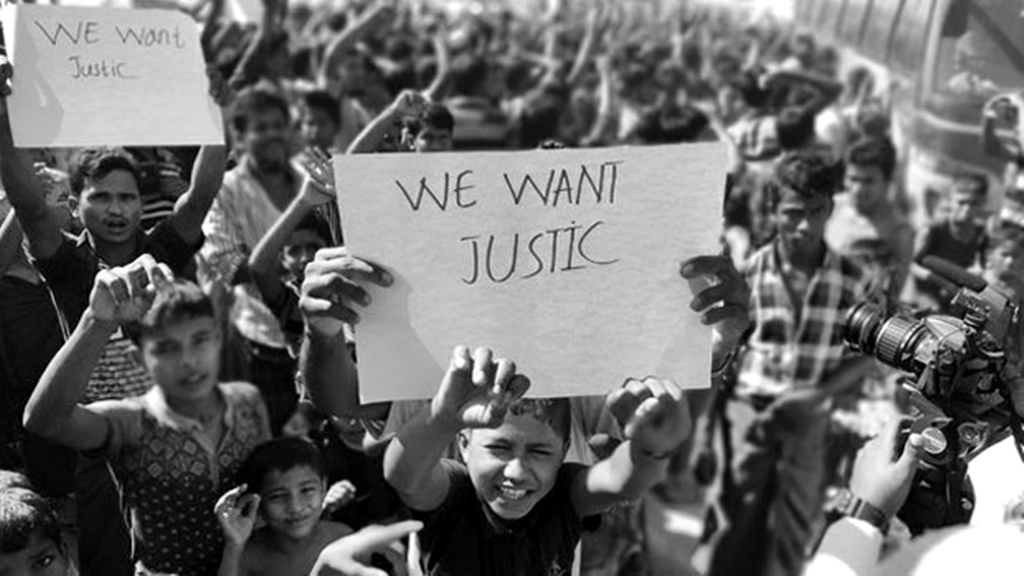

Leaders of the Rohingya refugee community in the camps said they had not been consulted on the matter and were unaware of plans for any imminent return.

Louise Donovan, a UNHCR spokeswoman in Cox’s Bazar, said: “If any express the intention to return voluntarily, UNHCR will meet with them on an individual basis and in a confidential setting to confirm the voluntariness of their decision and complete a voluntary repatriation form. The refugees will make the decision themselves.” She emphasized that “refugees who decide to exercise their right to return must be able to return to their places of origin or a place of their choice.”

However, the situation is complex as UNHCR have no access to Rahkine state so are unable to verify firsthand the conditions the Rohingya would be returning to. “Responsibility for ensuring conditions are conducive for safe and dignified return rests with Myanmar,” said Donovan.

Tens of thousands of Rohingya remain inside Myanmar, confined to camps and villages across Rakhine state where they are denied citizenship and their movements restricted.

The U.N. has said conditions in Rakhine state, where government troops have been enveloped in a new war, with government troops fighting Arakan Army, are not conducive for the return of refugees.

A U.N. investigator said in July that human rights violations against civilians by security forces and Arakan Army may amount to fresh war crimes, citing reports of deaths during army interrogations. Myanmar authorities have blocked most humanitarian agencies, including the U.N., from the area.

A recent report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) found “no evidence of widespread preparation for Rohingya refugees to return to safe and dignified conditions.” Instead it revealed that the burning and destruction of Rohingya villages by security forces had continued until this year, and that there were no homes for the Rohingya to return to, just large-scale camps, and six new military bases.

While the UN conditions for the return of the Rohingya is that it is “voluntary, safe and dignified” and that their rights and freedoms will be secured once they are back in Myanmar, there is no evidence to show this will be the case.

Moreover, according to UNHCR’s statute:-

• Repatriation should be voluntary, which includes two elements: freedom of choice and an informed decision

• repatriation should take place under conditions of safety and dignity:

• safety and dignity in connection with voluntary repatriation focuses on the repatriation process itself and after return

• the two voluntary repatriation methods commonly distinguished are organized and Spontaneous

Voluntary

The decision to repatriate should be a voluntary one. This requirement is more than a matter of principle, a return which is voluntary is more likely to be lasting and sustainable. A voluntary decision implies two elements: freedom of choice (which relates to the situation in the country of asylum) and an informed decision (which relates to the situation in the country of origin). As a general rule, UNHCR should be convinced that the positive pull-factors in the country of origin are an overriding element in the refugees’ decision to return, rather than possible push factors in the host country or negative pull-factors, such as threats to property, in the home country.

Safety and Dignity

Repatriation should not only be voluntary, it should take place under conditions of safety and dignity.

Safety

Return in safety is one that takes place under conditions of Legal safety: such as amnesties, public assurances of personal safety, integrity, freedom from fear of persecution or arbitrary punishment on return, citizenship status, Physical security: including protection from armed attacks and mines and Material security: access to land and property, means of a livelihood and for children an education as well.

Dignity

The concept of dignity is less self-evident than safety. The dictionary definition of dignity contains elements of “serious, composed, worthy of honour and respect.” In practice it means that refugees are not manhandled, that they can return unconditionally and if they are doing so spontaneously they can do so at their own pace, that they are not arbitrarily separated from family members; and that they are treated with respect by the authorities and full acceptance by the national authorities, including the full restoration of their rights.

Thus, the repatriation must be voluntary, safe and dignified, otherwise, the hastily repatriation process might paved the way to all the Rohingya refugees for jumping from the frying-pan to the fire.