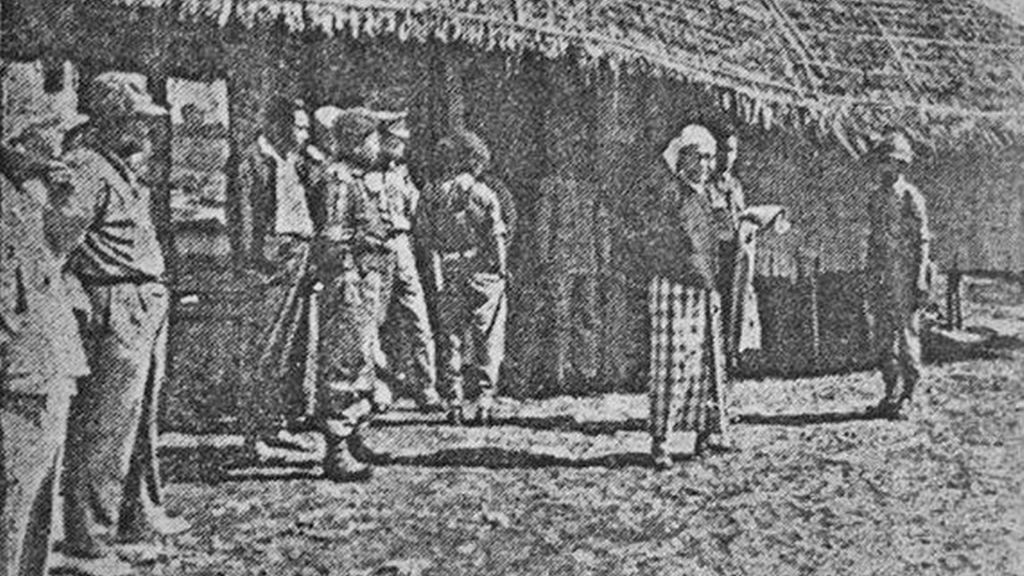

The Rohingyas Welcomed PMU Nu’s Visit

- 05/04/2019

- 0

By Aman Ullah

The then Prime minister of Burma U Nu visited to Akyab and Maungdaw on 27-28 January 1961 there the local peoples including the Rohingyas warmly received him.

About U Nu

U Nu (1907-1995) was the first prime minister of independent Burma (now called Myanmar) after freedom was obtained in 1948 from British colonial rule. He was also a leader of the Buddhist revival and a noted writer. After being ousted by the military in 1962, he remained an opposition leader in exile and a proponent of democracy for Myanmar until his death.

Born in the Burmese village of Wakema on May 25, 1907, U Nu was the son of a minor nationalist politician. Educated in Wakema and at Myoma National High School in Rangoon, Nu graduated in 1929 from the University of Rangoon, where one of his friends was U Thant, later secretary general of the United Nations. Nu spent five years as a teacher and journalist before returning to Rangoon University in 1934 to pursue a law degree.

Nu first came to national attention as a leader of the 1936 students’ strike, which was the first mass demonstration of Burmese opposition to British colonial rule. For his revolutionary agitation, he was expelled by the British from the university’s law school. A writer and translator of considerable talent, Nu in the late 1930s was the major force behind the Red Dragon Book Club, which published and distributed revolutionary literature. In 1942 he was imprisoned by the British.

Reluctant Leader

Released after the Japanese invaded, U Nu served as foreign minister and information minister in the Japanese-installed government of the nationalist leader Ba Maw. But even while serving in the puppet government, U Nu was organizing an anti-Japanese guerilla force. Nu’s perceptive account of these years, Burma under the Japanese, was published in the United States in 1954. After the war, Nu, who was a devout Buddhist, attempted to retire to a life of meditation and writing. But when an elected delegate to the constitutional convention died in a drowning accident, Nu was elected in a special by-election in 1947 to succeed him.

Later elected president of the Constituent Assembly, Nu was a secondary figure to Aung San, independent Burma’s “founding father.” Nu was not even a member of the interim government that was preparing to succeed the British rulers. But on July 19, 1947, Aung San and most of the other top nationalist leaders were savagely slain by a crazed political rival. The last British governor, Sir Hubert Rance, immediately called on Nu to step into Aung San’s shoes as premier-designate of independent Burma. With sorrow and reluctance, Nu became independent Burma’s first prime minister when colonial rule ended on January 4, 1948. Nu, who negotiated the final terms of Burmese independence, chose to lead his country out of the British Commonwealth entirely.

Architect of Neutrality

For ten years (1948-1958), with a brief break in 1956 to reorganize the government political party, U Nu was Burma’s premier and architect of a foreign policy that avoided commitment to either the American or Soviet sides in the Cold War. Widely acclaimed by the Burmese masses for his devotion to Buddhism, Nu held out successfully against a variety of Communist and ethnic minority rebellions. He also tried, with some success, to modernize his country economically and establish a socialist state.

Known outside Burma primarily for his political career, U Nu was the major force behind the nation’s post-colonial Buddhist revival. In 1954-1956, he convened the Sixth Great Buddhist Synod, a major international gathering of Buddhists.

Nu was also a prolific writer of fiction, plays, and political commentary. Probably the best of his works were written before World War II: Ganda-layit, based on a 1939 trip to China, and Modern Plays, a perceptive series of political parables. In 1952 he wrote The People Win Through, subsequently produced as a motion picture, as part of the government’s effort to neutralize Communist propaganda. The Wages of Sin, staged in 1961, attacked corruption and self-seeking among government officials.

Opposing the Military.

In 1958 Nu was toppled from power in a bloodless coup led by Gen. Ne Win, commander in chief of the armed forces. Courageously attacking the new regime, Nu convinced the military to hold elections and return the civilians to office. In February 1960 Nu’s party, although harassed by the army, won the most lopsided victory in the country’s history.

U Nu was less effective during his second stint as premier, as economic and minority problems worsened. In March 1962, Gen. Ne Win and his army ousted Nu for a second time. From March 1962 to October 1966, Nu was kept in virtual solitary confinement by the very Burmese government he had helped to bring into being. Following his unexplained release by Gen. Ne Win in 1966, Nu slowly returned to public activity. By 1968, Nu was raising funds for the victims of a typhoon.

Deteriorating economic and other circumstances led Ne Win in late 1968 to create a National Unity Advisory Board, and he included U Nu among its 33 members. Nu demanded a return to parliamentary democracy, and by April 1969 he feared he would be again imprisoned or even killed. Feigning illness, he escaped to India.

In August 1969 U Nu set out on a world tour to mobilize international opinion against continued military rule in his country. In London he announced the formation of a new party, the Parliamentary Democracy party, to restore representative government in Burma. A party headquarters and a de facto government-in-exile were established in Bangkok, capital of neighboring Thailand. From there he led the opposition movement until 1973, when he was forced to leave Thailand and move to the United States. In 1988, when a democratic uprising finally ousted Ne Win’s regime, U Nu proclaimed himself prime minister of a “parallel government,” but the military quickly placed under house arrest Nu and other opposition leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, who won the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize. Nu was released in 1992 and spent his last years in seclusion until his death in February 1995.