Traffickers: Selling False Dreams To The Rohingya

- 16/12/2020

- 0

By Athira Nortajuddin, The ASEAN Post

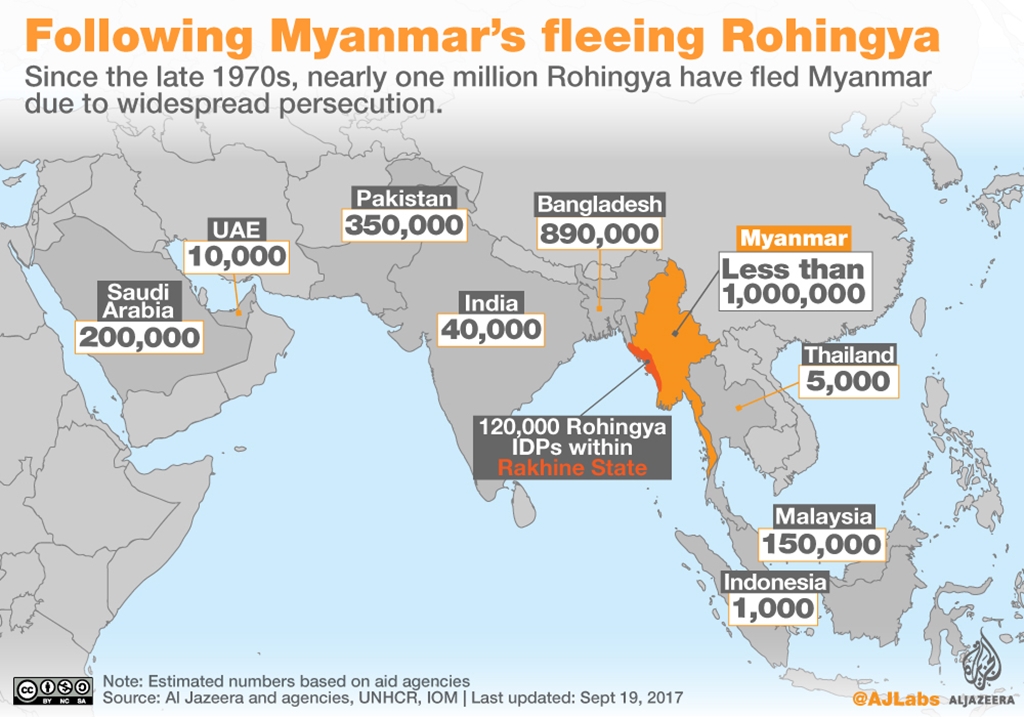

From Rakhine state in Myanmar, the Rohingya are an ethnic community of largely Muslim people. Perhaps a million of them have fled from violence in the ASEAN member state in successive waves of displacement since the early 1990s. In 2017, hundreds of thousands more fled Myanmar to escape persecution, war crimes and alleged genocide.

Today, over 900,000 Rohingya live in camps in Cox’s Bazar in southeast Bangladesh – the world’s largest refugee settlement. Some have escaped to other neighbouring countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia – said to be among the Rohingya’s favoured destinations.

As of February, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that about 178,990 refugees and asylum seekers have registered with the agency in Malaysia. The majority are from Myanmar, comprising some 101,010 Rohingya. In September, 300 Rohingya refugees landed in Indonesia – the biggest single arrival of refugees in the populous archipelago since 2015.

It was reported that they set sail from southern Bangladesh at the end of March or early April, bound for Malaysia, but were turned back by Malaysian authorities.

Earlier this year when the coronavirus outbreak spread outside of China, countries around the world scrambled to implement preventive measures such as closed borders, lockdowns and restricted movements. Therefore, Malaysia – like other nations battling the pandemic – turned away boats carrying Rohingya refugees in April and later in June due to COVID-19 fears. Neighbouring Thailand also denied entry to the refugees because of coronavirus restrictions.

Abuse On Boat

Just yesterday, international news agency AFP released a video of smugglers beating Rohingya refugees on a trafficking boat. Filmed on a mobile phone by a smuggler who later fled the vessel, the video shows dozens of asylum seekers, including children, sitting in the hull and on the deck as smugglers stand among them.

The footage was shot several days before the group’s Malaysia-bound boat returned to Bangladesh in mid-April.

“They started beating us because we complained about the food,” said Mohammad Osman, a 16-year-old passenger.

“They randomly beat us just because we were asking for more rice and water,” he added.

Osman’s neighbour, Enamul Hasan, who was also on the ship, said he grabbed the phone after one of the smugglers who left it behind when fleeing onto another vessel during what amounted to a mutiny.

Hasan told AFP that some Rohingya died at the hands of the criminals. “They beat us mercilessly – hitting our heads, tearing at our ears, breaking hands.”

The two men claimed that 46 people on their vessel died from beatings, starvation and illness.

“We realised if this continues, we all would die. We needed to do something. We felt like we were in hell,” explained Hasan.

“So, we attacked the crew since we had nothing to lose. It was a life-or-death situation… we threatened to kill the smugglers if they didn’t drop us on land.”

The smugglers responded to the mutiny by threatening to set the boat on fire – but instead left the refugees back near Bangladesh and fled.

Human Trafficking

Sunai Phasuk, senior researcher at international human rights non-governmental organization (NGO), Human Rights Watch’s Asia division noted that traffickers usually prey on desperation, employing brutal tactics to exploit and extort without accountability and they are organised across every level. The Rohingya, said to be “the most discriminated people in the world” are among their victims.

In its report titled, “The Human Trafficking of Rohingya,” humanitarian organisation Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) explained that traffickers sometimes begin operating in Rakhine state by making promises to the Rohingya that they will be provided with an escape route, on ships that will bring them to safer destinations and better lives for a certain amount of money.

However, as the Rohingya are very poor and unable to make such payments, they end up in a kind of bondage agreement with the traffickers. This often leads to them being subject to slave-like conditions.

Another scenario that also happens is that the Rohingya are asked to make payment as soon as they embark on a trafficking boat, failing which they will be thrown overboard. The traffickers sometimes threaten to go after the rest of their families as well.

“I was told I’d get the opportunity to finish my studies and earn money to get my family out of poverty,” said Hasan in an interview with AFP, recounting dreams and promises that were sold by a low-level smuggler in the refugee camp who was his main contact point for the trip.

Instead, they were delivered to violence and extortion. “I will never forget what I’ve been through. The traffickers, the brutality of the sailors… I’d never do it again,” he continued.

The United Nations (UN) also said that desperate men, women and children are being recruited with false offers of paid work in various industries such as fishing, small commerce, begging and, in the case of girls, domestic work. With no alternative source of income, the refugees are willing to take whatever opportunities are presented to them.

But once they start work, they find that they are not paid what was promised. Some were even forced into jobs they never agreed to do. The UN cited a case where a number of adolescent girls, who were promised work as domestic helpers in Cox’s Bazar and Chittagong, were forced into prostitution.